Ariel (księżyc)

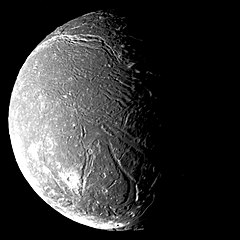

Mozaika najlepszych zdjęć Ariela uzyskanych przez sondę Voyager 2 | |

| Planeta | |

|---|---|

| Odkrywca | |

| Data odkrycia | 24 października 1851 |

| Charakterystyka orbity | |

| Półoś wielka | 190 900 km[1] |

| Mimośród | 0,0012[1] |

| Okres obiegu | 2,520 d[1] |

| Nachylenie do płaszczyzny równika planety | 0,041°[1] |

| Długość węzła wstępującego | 22,394°[1] |

| Argument perycentrum | 115,349°[1] |

| Anomalia średnia | 39,481°[1] |

| Własności fizyczne | |

| Średnica równikowa | 1158 km |

| Masa | (1,35 ± 0,12) ×1021 kg |

| Średnia gęstość | 1,67 g/cm³ |

| Przyspieszenie grawitacyjne na powierzchni | 0,27 m/s² |

| Siła ciążenia na powierzchni | 0,028 g |

| Prędkość ucieczki | 0,56 km/s |

| Okres obrotu wokół własnej osi | synchroniczny |

| Albedo | 0,39 |

| Jasność obserwowana (z Ziemi) | |

| Temperatura powierzchni | 58 K |

Ariel (Uran I ) – jeden z pięciu największych satelitów Urana. Został odkryty przez Williama Lassella w 1851, równocześnie z Umbrielem. Wszystkie duże księżyce Urana są zbudowane z około 40–50% zamrożonej wody zmieszanej ze skałami, są to nieco większe kawałki skał niż na dużych księżycach Saturna takich jak Rea. Powierzchnia Ariela jest pokryta kraterami oraz głębokimi (nawet do 10 km), długimi na setki kilometrów wąwozami. Ariel jest bardzo podobny do Tytanii, lecz jego powierzchnia jest bardziej urozmaicona, zaś kratery i wąwozy są tu dużo większe i bardziej rozwinięte. Powierzchnia jest stosunkowo młoda (jej wiek jest porównywalny z wiekiem powierzchni Enceladusa), niektóre procesy tworzące nową powierzchnię są w toku.

Nazwa

Nazwy tego oraz pozostałych czterech największych satelitów Urana zostały zaproponowane przez Johna Herschela (syna odkrywcy Urana) w 1852 r. na życzenie Williama Lassella, który rok wcześniej odkrył Ariela oraz Umbriela. Lassell poparł schemat nazewnictwa Herschela dla siedmiu ówcześnie znanych satelitów Saturna oraz nazwał ósmego odkrytego przez siebie Hyperiona w ramach tego schematu.

Wszystkie księżyce Urana nazwane są imionami postaci z dzieł Williama Szekspira lub Alexandra Pope’a. Nazwa Ariel pochodzi od imienia ducha powietrza ze sztuki Szekspira – Burza i poematu Pukiel porwany (The Rape of the Lock) Pope’a[3].

Właściwości fizyczne

Jedyne wysokiej jakości zdjęcia Ariela pochodzą z sondy kosmicznej Voyager 2, która sfotografowała księżyc podczas przelotu w okolicy Urana w styczniu 1986 r. Wówczas południowa półkula księżyca była skierowana ku Słońcu, więc tylko ta część jest widoczna. Ariel jest księżycem lodowym, składa się z lodu w około 70%, w 30% z krzemianów. Na jego lodowej powierzchni często występują kratery, które pokryte są nieznanym ciemnym materiałem.

Naukowcy rozpoznają jedynie trzy typy struktur geologicznych Ariela:

- kratery uderzeniowe

- wąskie depresje

- doliny

Zobacz też

- Ukształtowanie powierzchni Ariela

- Największe księżyce Urana: Miranda, Umbriel, Tytania, Oberon

- Chronologiczny wykaz odkryć planet, planet karłowatych i ich księżyców w Układzie Słonecznym

Przypisy

- ↑ a b c d e f g Planetary Satellite Mean Orbital Parameters (ang.). Jet Propulsion Laboratory, 2011-12-14. [dostęp 2012-10-09].

- ↑ Planetary Satellite Physical Parameters (ang.). Jet Propulsion Laboratory, 2015-02-19. [dostęp 2016-09-12].

- ↑ The Moons of Uranus (ang.). Space Today Online. [dostęp 2013-06-01].

Linki zewnętrzne

- Ariel (ang.). W: Solar System Exploration [on-line]. NASA. [dostęp 2018-12-25].

Media użyte na tej stronie

This is a revised version of Solar_System_XXIX.png.

This image of Uranus was compiled from images returned Jan. 17, 1986, by the narrow-angle camera of Voyager 2. The spacecraft was 9.1 million kilometers (5.7 million miles) from the planet, several days from closest approach. This picture has been processed to show Uranus as human eyes would see it from the vantage point of the spacecraft. The picture is a composite of images taken through blue, green and orange filters. The darker shadings at the upper right of the disk correspond to the day-night boundary on the planet. Beyond this boundary lies the hidden northern hemisphere of Uranus, which currently remains in total darkness as the planet rotates. The blue-green color results from the absorption of red light by methane gas in Uranus' deep, cold and remarkably clear atmosphere.

This mosaic of the four highest-resolution images of Ariel represents the most detailed Voyager 2 picture of this satellite of Uranus. The images were taken through the clear filter of Voyager's narrow-angle camera on Jan. 24, 1986, at a distance of about 130,000 kilometers (80,000 miles). Ariel is about 1,200 km (750 mi) in diameter; the resolution here is 2.4 km (1.5 mi). Much of Ariel's surface is densely pitted with craters 5 to 10 km (3 to 6 mi) across. These craters are close to the threshold of detection in this picture. Numerous valleys and fault scarps crisscross the highly pitted terrain. Voyager scientists believe the valleys have formed over down-dropped fault blocks (graben); apparently, extensive faulting has occurred as a result of expansion and stretching of Ariel's crust. The largest fault valleys, near the terminator at right, as well as a smooth region near the center of this image, have been partly filled with deposits that are younger and less heavily cratered than the pitted terrain. Narrow, somewhat sinuous scarps and valleys have been formed, in turn, in these young deposits. It is not yet clear whether these sinuous features have been formed by faulting or by the flow of fluids.

Diameter comparison of the Uranian moon Ariel, Moon, and Earth.

Scale: Approximately 28.9 km per pixel.