Instrumentalne pomiary temperatury

Instrumentalne pomiary temperatury – w meteorologii i klimatologii, pomiary temperatury atmosfery i oceanów bezpośrednio z użyciem termometrów. Są jednym z głównych źródeł wiedzy o klimacie Ziemi, w ostatnich dekadach coraz częściej uzupełnianym pomiarami satelitarnymi w podczerwieni oraz wykonywanymi przez sondy zanurzeniowe i sondy atmosferyczne.

Historia

Pomiary temperatury powietrza przy użyciu termometrów wykonywane są regularnie od XVII wieku. Najstarsza nieprzerwana seria pomiarowa pochodzi ze środkowej Anglii i zawiera dane od 1659 roku[1]. Pomiary wykonywane są przy użyciu termometrów rtęciowych lub alkoholowych (a współcześnie również termometrów elektronicznych), które są wzorcowane przez porównanie do stałych, niezmiennych wartości temperatury, takich jak punkt potrójny wody, czy temperatura topnienia określonych metali. Liczba stacji pomiarowych rośnie, lecz tylko niewiele może pochwalić się nieprzerwaną serią pomiarów od XIX wieku. Wystarczające dane do określenia średniej temperatury globu, zwanej temperaturą globalną, istnieją od około 1850 roku[2].

Wartość bezwzględna i anomalie

Zarówno w meteorologii, jak i w klimatologii znacznie częściej od wartości bezwzględnych korzysta się z anomalii. Chwilowa anomalia temperatury wynika przede wszystkim z bieżącej sytuacji meteorologicznej, stąd dla blisko położonych stacji meteorologicznych wartości anomalii są zazwyczaj zbliżone, podczas gdy wartości bezwzględne mogą się znacznie różnić (szczególnie w sytuacji np. dużej różnicy wysokości). Średnia anomalia temperatury dla dłuższego okresu (miesiąc, rok), pozwalają określić charakterystykę meteorologiczną danego okresu, co ma wpływ m.in. na wzrost roślin. Długoterminowe (powyżej 30 lat) instrumentalne pomiary pozwalają określić klimat danej stacji meteorologicznej a nawet określić jego zmiany.

Linie pomiarowe

W przypadku stacji pomiarowych działających przez długi czas dostępne są linie pomiarowe pokazujące przebieg temperatury (w tym średnie wartości miesięczne i roczne) na przestrzeni dekad. Określenie średniej temperatury na dużym obszarze, lub średniej temperatury globalnej wymaga uwzględnienia danych z wielu miejsc pomiaru. Ponieważ rozmieszczenie stacji pogodowych nie jest równomierne, najwyższą wagę przyznaje się pomiarom z miejsc, dla których liczba pomiarów jest niewielka. Dla tych miejsc niepewność danych jest największa[4]. W przypadku pomiarów satelitarnych największa niepewność występuje dla obszarów Arktyki i Antarktyki, które są niedostępne dla większości satelitów ze względu na ich orbitę. Wartości średniej temperatury globalnej wyznaczone na podstawie instrumentalnych pomiarów temperatury mogą się nieznacznie różnić w zależności od przyjętej metody interpolacji danych na obszary bez bezpośrednich pomiarów.

Ocieplenie klimatu

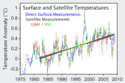

Instrumentalne pomiary temperatury są jednym z głównych źródeł informacji o klimacie w XIX i XX wieku. Począwszy od lat 70' XX wieku dysponujemy satelitarnymi pomiarami promieniowania podczerwonego, które można wykorzystać do wyliczenia temperatury. Ze względu na to, że promieniowanie pochodzi z całej atmosfery a nie tylko samej powierzchni Ziemi, to są one obarczone sporymi niepewnościami. Dodatkowo obliczenia temperatury na podstawie promieniowania muszą uwzględniać takie czynniki jak np. zmianę wysokości satelity. Temperaturę we wcześniejszym okresie można szacować na podstawie danych pośrednich (ang. proxy)[5]. Strona internetowa[6] National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration zawiera szczegółowe wyniki rokrocznych pomiarów temperatury lądu i oceanów od 1880[7]. Tabela po prawej stronie przedstawia 10 najcieplejszych lat w historii pomiarów instrumentalnych wg danych NOAA, w trzeciej kolumnie umieszczono średnią anomalię temperatury dla poszczególnych lat względem średniej z XX wieku.

| Pomiary instrumentalne | Trend (°C) |

|---|---|

| NOAA | +0,171 |

| GISS (NASA) | +0,185 |

| HadCRUT (UK Met Office) | +0,171 |

| Berkeley (temperatura powietrza) | +0,188 |

| Berkeley (temperatura wody) | +0,165 |

| JMA (Japonia) | +0,138 |

| Pomiary satelitarne | |

| RSS | +0,206 |

| UAH | +0,130 |

| Miejsce | Rok | Anomalia °C |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2016 | 1,00 |

| 2 | 2020 | 0,98 |

| 3 | 2019 | 0,95 |

| 4 | 2015 | 0,93 |

| 5 | 2017 | 0,91 |

| 6 | 2018 | 0,83 |

| 7 | 2014 | 0,74 |

| 8 | 2010 | 0,72 |

| 9 | 2013 | 0,68 |

| 10 | 2005 | 0,67 |

Przypisy

- ↑ G. Manley, "Central England Temperatures: monthly seans 1659 to 1973", Quaterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society, wyd. 100, str. 389-405 (1974). rmets.org.uk. [zarchiwizowane z tego adresu (2014-02-03)].

- ↑ Brohan, P., J.J. Kennedy, I. Harris, S.F.B. Tett, P.D. Jones (2006). "Uncertainty estimates in regional and global observed temperature changes: a new dataset from 1850". Journal of Geophysical Research, wyd. 111

- ↑ Temperature data (HadCRUT, CRUTEM, HadCRUT5, CRUTEM5), Climatic Research Unit (University of East Anglia) and Met Office [dostęp 2021-05-15] (ang.).

- ↑ Past reconstructions: problems, pitfalls and progress, RealClimate.org [dostęp 2021-05-15] (ang.).

- ↑ Metody badania dawnego klimatu, ZiemiaNaRozdrozu.pl [dostęp 2021-05-15] (pol.).

- ↑ Climate Monitoring; State of the Climate

- ↑ Climate at a Glance | National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI), www.ncdc.noaa.gov [dostęp 2017-11-24] (ang.).

- ↑ Global Climate Report - Annual 2020. [dostęp 2021-02-06].

Media użyte na tej stronie

Land-ocean temperature index, 1880 to present, with base period 1951-1980. The solid black line is the global annual mean and the solid red line is the five-year lowess smooth. The blue uncertainty bars represents the total (LSAT and SST) annual uncertainty at a 95% confidence interval. [More information on the updated uncertainty model can be found here: Lenssen et al. (2019).]

Autor: Dobrzejest, wikipedia.pl : Adi4000, Licencja: CC-BY-SA-3.0

This image shows the instrumental record of global average temperatures as compiled by the Climatic Research Unit of the University of East Anglia and the Hadley Centre of the UK Meteorological Office. Data set HadCRUT3 was used. HadCRUT3 is a record of surface temperatures collected from land and ocean-based stations. The most recent documentation for this data set is Brohan, P., J.J. Kennedy, I. Haris, S.F.B. Tett and P.D. Jones (2006). "Uncertainty estimates in regional and global observed temperature changes: a new dataset from 1850". J. Geophysical Research 111: D12106. DOI:10.1029/2005JD006548. Following the common practice of the IPCC, the zero on this figure is the mean temperature from 1961-1990.

Autor: Robert A. Rohde, Licencja: CC-BY-SA-3.0

- Jones, P.D. and Moberg, A. (2003). "Hemispheric and large-scale surface air temperature variations: An extensive revision and an update to 2001". Journal of Climate 16: 206-223.

- Christy, J.R., R.W. Spencer, W.B. Norris, W.D. Braswell and D.E. Parker (2003). "Error estimates of version 5.0 of MSU/AMSU bulk atmospheric temperatures". J. Atmos. Oceanic Technol. 20: 613-629.

- Fu, Q., Johanson, C. M., Warren, S. G. & Seidel, D. J. (2004). "Contribution of stratospheric cooling to satellite-inferred tropospheric temperature trends". Nature 429: 55−58.

- Mears, Carl A. and Frank J. Wentz (2005). "The Effect of Diurnal Correction on Satellite-Derived Lower Tropospheric Temperature". Science Express: published online 11 August 2005.

- Matthias C. Schabel, Carl A. Mears, Frank J. Wentz (2002). "Stable Long-Term Retrieval of Tropospheric Temperature Time Series from the Microwave Sounding Unit". Proceedings of the International Geophysics and Remote Sensing Symposium III: 1845-1847.