Krzywa Phillipsa

Krzywa Phillipsa – krzywa ilustrująca statystyczną zależność pomiędzy stopą bezrobocia a inflacją płac (tempem wzrostu wynagrodzeń).

Opis

Krzywa ta została po raz pierwszy opisana w artykule nowozelandzkiego ekonomisty (wykładającego w Wielkiej Brytanii) Albana W. Phillipsa w 1958 roku[1]. Przedstawiała ona ujemną korelację między stopą bezrobocia i tempem wzrostu płac w Wielkiej Brytanii w latach 1861−1957[2].

Istnienie zaobserwowanej przez Philipsa na przestrzeni blisko 100 lat zależności sugerowało, że możliwe jest osiągnięcie niższego poziomu bezrobocia kosztem wyższej inflacji. Wielu ekonomistów wierzyło, że relacja ta ma charakter uniwersalny i jest rodzajem prawa ekonomicznego. Poglądy te miały wpływ na politykę gospodarczą rządów wielu państw, które decydowały się na celowe utrzymywanie wyższej inflacji dążąc do obniżenia bezrobocia. Począwszy od końca lat 60. XX wieku zależność ta przestała się jednak sprawdzać (następował jednoczesny wzrost inflacji i bezrobocia) i przez to sposób walki z bezrobociem poprzez zwiększanie inflacji spotykał się z coraz większą krytyką ekonomistów.

Pod koniec lat 60. Milton Friedman i Edmund S. Phelps zaczęli kwestionować pogląd o istniejącej ujemnej zależności między bezrobociem i inflacją[3][4]. Wbrew obowiązującemu konsensusowi dowodzili, że wymienność ta w dłuższym okresie nie ma ekonomicznego uzasadnienia, ponieważ uczestnicy rynku skorygują swoje zachowania w następstwie wzrostu inflacji, uwzględniając zmianę tempa wzrostu cen i w konsekwencji spadek bezrobocia będzie jedynie przejściowy (pionowa długookresowa krzywa Philipsa, zależność opisana przez Philipsa, może wystąpić jedynie w krótkim okresie).

W latach 70. krytyka krzywej Phillipsa stała się powszechna w związku z pojawieniem się, głównie w Anglii i w Stanach Zjednoczonych, zjawiska stagflacji. Polegało ono na utrzymywaniu się zarówno wysokiej inflacji, jak i wysokiego bezrobocia, co było zaprzeczeniem wniosków płynących z analizy krzywej Phillipsa.

Współczesne próby wyjaśnienia związku inflacji i bezrobocia

- NAIRU (non-accelerating-inflation rate of unemployment) − koncepcja bazująca m.in. na pracach Friedmana[5] odnosząca się do zależności między bezrobociem a inflacją.

- Teoria racjonalnego wyboru − oparta na teorii gier.

Nagrody Nobla

Wiele spośród analiz krzywej Phillipsa znalazło swe uznanie w Nagrodzie Nobla. Nagrodzeni m.in. za pracę nad zjawiskiem inflacji i bezrobocia[6]:

- Friedrich Hayek i Gunnar Myrdalw 1974

- Milton Friedman w 1976

- Robert Lucas w 1995 − za rozwinięcie tez Milton Friedmana i Edmund Phelpsa znaną dziś jako Krytyka Lucasa

- Edward Prescott w 2004

- Edmund Phelps w 2006

- Christopher Sims i Thomas Sargent w 2011

Przypisy

- ↑ Simon Cox (ed.): Economics. Making sense of the Modern Economy. London: Profile Books, 2006, s. 184. ISBN 978-1-86197-606-2.

- ↑ Alban William Phillips. The Relation between Unemployment and the Rate of Change on Money Wage Rates in the United Kingdom 1861–1957. „Economica”. 25 (100), s. 283-299, 1958.

- ↑ Milton Friedman, A monetary History of the United States, 1867-1960

- ↑ Phelps, Edmund S. (1968). "Money-Wage Dynamics and Labor Market Equilibrium". Journal of Political Economy 76: 678-711

- ↑ Friedman, Milton. 1968. "The Role of Monetary Policy." American Economic Review 58 (March): 1 – 17.

- ↑ Brian Domitrovic, https://www.forbes.com/sites/briandomitrovic/2011/10/10/the-economics-nobel-goes-to-sargent-sims-attackers-of-the-phillips-curve/ The Economics Nobel Goes to Sargent & Sims: Attackers of the Phillips Curve, 10 October

Bibliografia

- David Begg, Stanley Fischer, Rudiger Dornbusch: Makroekonomia. Warszawa: Polskie Wydawnictwo Ekonomiczne, 2007. ISBN 978-83-208-1644-0.

- Michael Burda, Charles Wyplosz: Makroekonomia. Podręcznik europejski. Warszawa: Polskie Wydawnictwo Ekonomiczne, 2000. ISBN 978-83-208-2032-4.

Media użyte na tej stronie

Krzywa Phillipsa

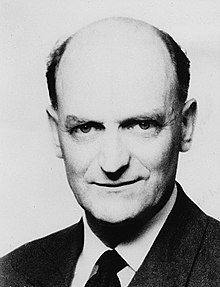

Autor: Library of the London School of Economics and Political Science, Licencja: No restrictions

Extracts from ‘The Phillips Machine Project’ by Nicholas Bar, LSE Magazine, June 1988, No75, p.3

A.W. H. ‘Bill’ Phillips is known worldwide as the originator of the Phillips Curve. Less well known is the remarkable man he was personally, and his extraordinary route to academic prominence via what came to be called the Phillips Machine.

Trained as an electrical engineer in his native New Zealand in the 1930s, he caught the travel bug and took up an engineering job in the Australian outback, where he also earned money by running a cinema and hunting crocodiles. He reached London in 1938 via the Trans-Siberian railway and joined the RAF at the outbreak of war. He was captured in Java and spent most of the war in a Japanese POW camp, where he learned Chinese and some Russian from fellow prisoners.

Back in Britain he took the BSc (Econ) 1946-49, special subject sociology. He developed a great interest in economics…and like many of his generation, became very caught up with Keynesian theory. Though fascinated he found the Keynesian model hard going. With Walter Newlyn (an undergraduate contemporary, later Professor of Economics at Leeds University) to help with the economic theory, he fell back on his engineering training. He saw that money stocks could be represented as tanks of water, and monetary flows by water circulating round plastic tubes.

With a grant of £100 (obtained with Newlyn’s help) he spent the summer of 1949 in a garage in Croydon ‘living on air’ as James Meade was later to put it, working on a hydraulic representation of the Keynesian model.

In the machine he constructed, the circular flow of income was represented by water being pumped round a series of clear plastic tubes, with outflows representing savings, taxes and imports, and inflows representing investment, government spending and exports. The model had three tanks representing the stock of money, one for transaction balances and one for foreign-held sterling balances. The whole system determined the level of income, the rate of interest, imports, exports and the exchange to an accuracy (astonishing at the time) of +two per cent. The time path of income and the other variables was traced out by plotter pens making it possible to analyse the quantitative effects of economic policy.

The machine, in the jargon, was a hydraulic representation of an open economy IS-LM model with an explicit underlying dynamic structure. It was this very Heath Robinson prototype which, with the enthusiastic support of James Meade (then Professor of Commerce at the School), Phillips demonstrated to Lionel Robbins’ seminar in November 1949. Those attending gazed in wonder at this large (7ft high x 5ft wide x 3ft deep) ‘thing’ in the middle of the room. Phillips, chain smoking, paced back and forth explaining it in a heavy New Zealand drawl, in the process giving one of the best lectures on Keynes that anyone in the audience had ever heard. Then he switched the machine on. And it worked! According to Lord Robbins’ recollections, “there was income dividing itself into consumption and saving…Keynes and Robertson need never have quarrelled if they had had the Phillips Machine before them”…Phillips was made an Assistant Lecturer in Economics in 1950, Lecturer 1951, Reader 1954, and Tooke Professor of Economic Science and Statistics in 1958 (the year his Phillips Curve paper was published). He took up a Chair at the Australian National University in 1967 and, having suffered a major stroke, retired to Auckland in 1970, where he died five years later aged 60, mourned by many friends for personal as much for professional reasons.’

IMAGELIBRARY/244