Lista największych gwiazd

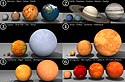

1. Merkury < Mars < Wenus < Ziemia,

2. Ziemia < Neptun < Uran < Saturn < Jowisz,

3. Jowisz < Wolf 359 < Słońce < Syriusz,

4. Syriusz < Polluks < Arktur < Aldebaran,

5. Aldebaran < Rigel < Antares < Betelgeza,

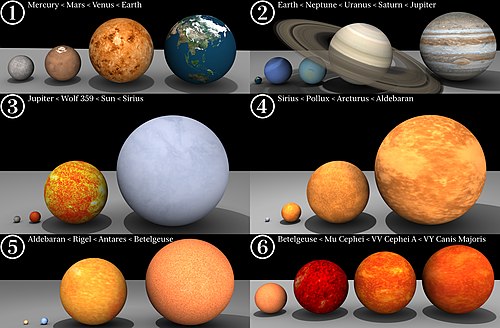

6. Betelgeza < Mi Cephei < VV Cephei A < VY Canis Majoris

Lista największych gwiazd – zestawienie gwiazd o największym stwierdzonym promieniu. Jednostką miary jest promień Słońca (1 R☉ = 695 700 km, czyli około 109 promieni Ziemi).

Kolejność listy i przynależność do niej poszczególnych gwiazd nie są pewne. W obliczeniach promienia występują wielkości obarczone dużą niepewnością, takie jak jasność gwiazdy i temperatura efektywna. Często promienie gwiazd można wyrazić tylko jako średnią lub zakres dopuszczalnych wartości. Wartości promieni gwiazd różnią się znacznie w źródłach i przy różnych metodach obserwacji.

Metody i problematyka

Za pomocą interferometrii można bezpośrednio zmierzyć średnice kątowe wielu gwiazd. Inne metody mogą wykorzystywać zakrycia przez Księżyc lub zaćmienia w układach podwójnych, które można wykorzystać do testowania pośrednich metod wyznaczania promieni gwiazd. Tylko kilka nadolbrzymów może zostać przesłoniętych przez Księżyc, w tym Antares A (Alfa Scorpii A). Przykładami zaćmieniowych układów podwójnych są Epsilon Aurigae (Almaaz), VV Cephei i V766 Centauri (HR 5171). W zależności od długości fali światła, w którym obserwowana jest gwiazda, granica bardzo rozrzedzonej atmosfery może być widoczna w różnej odległości od środka jej tarczy, dlatego pomiary średnicy kątowej mogą być niespójne.

Przy określaniu promieni największych gwiazd występują złożone problemy. Promienie lub średnice gwiazd są zwykle wyprowadzane w przybliżeniu przy użyciu prawa Stefana-Boltzmanna dla wydedukowanej jasności gwiazdy i efektywnej temperatury powierzchni. Odległości gwiazd i ich niepewność w przypadku większości gwiazd pozostają słabo określone. Wiele gwiazd nadolbrzymów ma rozdęte atmosfery i wiele znajduje się w nieprzezroczystych obłokach pyłu, co utrudnia wyznaczenie ich rzeczywistej temperatury efektywnej. Te atmosfery mogą również zmieniać się znacząco w czasie, regularnie lub nieregularnie pulsując w czasie kilku miesięcy lub lat – są to gwiazdy zmienne. To sprawia, że jasności gwiazd są określone z małą dokładnością, a to może znacząco zmieniać podane promienie.

Inne bezpośrednie metody określania promieni gwiazd polegają na zakryciach przez Księżyc lub zaćmieniach w układach podwójnych, które obserwuje się tylko dla bardzo małej liczby gwiazd.

Na tej liście znajdują się bardzo odległe gwiazdy pozagalaktyczne, które mogą mieć nieco inne właściwości i naturę niż obecnie największe znane gwiazdy w Drodze Mlecznej. Podejrzewa się, że niektóre czerwone nadolbrzymy w Obłokach Magellana mają nieco inne graniczne temperatury i jasność. Takie gwiazdy mogą przekraczać dopuszczalne granice, przechodząc duże erupcje lub zmieniając swoje typy widmowe w ciągu zaledwie kilku miesięcy. W Obłokach Magellana skatalogowano wiele czerwonych nadolbrzymów, z których wiele przekracza 700 promieni Słońca. Największe z nich mają około 1200–1300 R☉, chociaż kilka ostatnich odkryć ukazuje gwiazdy osiągające rozmiary >1500 R☉[1][2].

Lista

| Nazwa gwiazdy | Promień [R☉] | Metoda[a] | Uwagi |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stephenson 2-18 | 2150[3] | L/Teff | W pobliżu masywnej gromady otwartej Stephenson 2, gdzie znajduje się 26 czerwonych nadolbrzymów |

| LGGS J004520.67+414717.3 | 1870[4]–2510[5]2126[6] | L/Teff | W Galaktyce Andromedy |

| VY Canis Majoris | 2069[7][8] | L/Teff | Opisywana jako największa znana gwiazda na podstawie ocen rozmiaru od 1800 do 2100 promieni Słońca[9]. Starsze oceny promienia były bardzo rozbieżne, od 600 R☉[10] po ponad 3000 R☉[11]. |

| IRAS 05346-6949 | 2064 | L/Teff | W Wielkim Obłoku Magellana |

| MY Cephei | 1134[12]–2061[9] | L/Teff | Starsze oceny sugerowały promień do 2440 R☉ przy założeniu znacznie niższej temperatury[13]. |

| WY Velorum A | 2028[14] | AD | Gwiazda zmienna symbiotyczna zawierająca czerwonego nadolbrzyma |

| LGGS J013414.27+303417.7 | 1953[5] | L/Teff | W Galaktyce Trójkąta |

| Orbita Saturna | 1940–2169 | Dla porównania | |

| LGGS J004105.97+403407.9 | 1915[5] | L/Teff | W Galaktyce Andromedy |

| RX Telescopii | 1898[14] | AD | |

| WOH S71 (LMC 23095) | 1896[2] | L/Teff | W Wielkim Obłoku Magellana |

| V538 Carinae | 1870[14]–2264[15] | AD | |

| LGGS J013339.28+303118.8 | 1863[5] | L/Teff | W Galaktyce Trójkąta |

| MG73 46 (MSX LMC 891) | 1838[2] | L/Teff | W Wielkim Obłoku Magellana |

| LGGS J004539.99+415404.1 | 1792[2]–2377[5] | L/Teff | W Galaktyce Andromedy |

| WOH G64 | 1784–2481[16]1788[17] | L/Teff | W Wielkim Obłoku Magellana |

| LGGS J013312.26+310053.3 | 1765[5] | L/Teff | W Galaktyce Trójkąta |

| WOH S274 | 1784[2] | L/Teff | W Wielkim Obłoku Magellana |

| UY Scuti | 1706 ± 192[18] | AD | Wartość obliczona dla odległości 2,9 kpc |

| HV 2242 (WOH S69) | 1645[2] | L/Teff | W Wielkim Obłoku Magellana |

| NML Cygni | 1639 - 2775[19] 1183[20] | L/Teff | |

| SMC 78282 (PMMR 198) | 1600[21] | L/Teff | W Małym Obłoku Magellana |

| HV 5993 (WOH S464) | 1531[2] | L/Teff | W Wielkim Obłoku Magellana |

| RSGC1-F01 | 1530[22] | L/Teff | W gromadzie otwartej RSGC1 |

| LGGS J004431.71+415629.1 | 1505[5] | L/Teff | W Galaktyce Andromedy |

| W61 8-88 (WOH S465) | 1491[2] | L/Teff | W Wielkim Obłoku Magellana |

| LGGS J004336.68+410811.8 | 1485[5] | L/Teff | W Galaktyce Andromedy |

| HV 888 (WOH S140) | 1477[23]–2377[24] | L/Teff | W Wielkim Obłoku Magellana |

| UCAC4 116-007944 (MSX LMC 810) | 1468[2] | L/Teff | W Wielkim Obłoku Magellana |

| W60 A78 (WOH S459) | 1445[2] | L/Teff | W Wielkim Obłoku Magellana |

| HV 12998 (WOH S369) | 1443[2] | L/Teff | W Wielkim Obłoku Magellana |

| W60 A72 (WOH S453) | 1441[2] | L/Teff | W Wielkim Obłoku Magellana |

| LGGS J013418.56+303808.6 | 1436[5] | L/Teff | W Galaktyce Trójkąta |

| LGGS J003951.33+405303.7 | 1425[5] | L/Teff | W Galaktyce Andromedy |

| WOH S286 | 1417[2] | L/Teff | W Wielkim Obłoku Magellana |

| AH Scorpii | 1411 ± 124[18] | L/Teff | Jasność w zakresie widzialnym zmienia się o prawie 3m, jasność bolometryczna o ok. 20%. Zmiany średnicy nie są pewne ze względu na równoczesne zmiany temperatury. |

| LGGS J004428.48+415130.9 | 1410[4]–1504[5] | L/Teff | W Galaktyce Andromedy |

| WOH S281 (IRAS 05261-6614) | 1376[24]–1459[2] | L/Teff | W Wielkim Obłoku Magellana |

| IRAS 05280-6910 | 1367[16]–1738[25] | L/Teff | W Wielkim Obłoku Magellana |

| S Persei | 1364 ± 6[26] | AD | Czerwony nadolbrzym w podwójnej gromadzie Perseusza. Levsque i in. (2005) obliczyli promienie 780 R☉ i 1230 R☉ w oparciu o pomiary w paśmie K w podczerwieni[27]. Starsze oceny dawały wartości sięgające 2853 R☉ przy założeniu wyższej jasności[28]. |

| LGGS J004306.62+413806.2 | 1346[5] | L/Teff | W Galaktyce Andromedy |

| RSGC1-F03 | 1325[3] | L/Teff | W gromadzie otwartej RSGC1 |

| LGGS J004438.65+412934.1 | 1320[5] | L/Teff | W Galaktyce Andromedy |

| PMMR 62 | 1313[21] | L/Teff | W Małym Obłoku Magellana |

| SW Cephei | 1308[14] | AD | |

| SMC 18136 (PMMR 37) | 1307[21] | L/Teff | W Małym Obłoku Magellana |

| LGGS J013318.20+303134.0 | 1295[5] | L/Teff | W Galaktyce Trójkąta |

| LMC 170079 | 1294[21] | L/Teff | W Wielkim Obłoku Magellana |

| LGGS J05294221-6857173 | 1292[29] | L/Teff | |

| Z Doradus | 1271[21] | L/Teff | W Wielkim Obłoku Magellana |

| LGGS J004312.43+413747.1 | 1270[4]–1630[5] | L/Teff | W Galaktyce Andromedy |

| LGGS J004632.18+415935.8 | 1265[5] | L/Teff | W Galaktyce Andromedy |

| LGGS J013412.27+305314.1 | 1258[5] | L/Teff | W Galaktyce Trójkąta |

| LGGS J013310.71+302714.9 | 1252[5] | L/Teff | W Galaktyce Trójkąta |

| LGGS J004514.91+413735.0 | 1250[4]–1575[5] | L/Teff | W Galaktyce Andromedy |

| LGGS J013403.73+304202.4 | 1249[5] | L/Teff | W Galaktyce Trójkąta |

| LGGS J004148.74+410843.0 | 1248[5] | L/Teff | W Galaktyce Andromedy |

| LGGS J004428.12+415502.9 | 1240[4]–1259[5] | L/Teff | W Galaktyce Andromedy |

| RSGC1-F09 | 1230[3] | L/Teff | W gromadzie otwartej RSGC1 |

| LGGS J004633.38+415951.3 | 1229[5] | L/Teff | W Galaktyce Andromedy |

| LGGS J004416.28+412106.6 | 1222[5] | L/Teff | W Galaktyce Andromedy |

| SMC 5092 (PMMR 9) | 1216[21] | L/Teff | W Małym Obłoku Magellana |

| LGGS J004125.23+411208.9 | 1200[4]–1602[5] | L/Teff | W Galaktyce Andromedy |

| LGGS J013423.29+305655.0 | 1199[5] | L/Teff | W Galaktyce Trójkąta |

| HV 2532 (WOH S287) | 1195[21] | L/Teff | W Małym Obłoku Magellana |

| LGGS J004506.85+413408.2 | 1194[5] | L/Teff | W Galaktyce Andromedy |

| HD 90587 | 1191[14] | AD | |

| HV 2084 (PMMR 186) | 1187[21] | L/Teff | W Małym Obłoku Magellana |

| LGGS J004503.35+413026.3 | 1174[5] | L/Teff | W Galaktyce Andromedy |

| LGGS J004304.62+410348.4 | 1171[5] | L/Teff | W Galaktyce Andromedy |

| LGGS J004524.97+420727.2 | 1170[4]–1476[5] | L/Teff | W Galaktyce Andromedy |

| LGGS J004047.82+410936.4 | 1167[5] | L/Teff | W Galaktyce Andromedy |

| Westerlund 1-26 | 1165–1221[30] | L/Teff | Nietypowa gwiazda o bardzo niepewnych właściwościach, silne radioźródło. Widmo promieniowania jest zmienne, ale jasność wydaje się stała. |

| LGGS J004138.35+412320.7 | 1159[5] | L/Teff | W Galaktyce Andromedy |

| LGGS J013353.91+302641.8 | 1157[5] | L/Teff | W Galaktyce Trójkąta |

| RSGC1-F08 | 1150[9] | L/Teff | W gromadzie otwartej RSGC1. |

| W60 B90 (WOH S264) | 1149[24]–2555[2] | L/Teff | W Wielkim Obłoku Magellana |

| LGGS J013356.84+304001.4 | 1149[5] | L/Teff | W Galaktyce Trójkąta |

| HD 62745 | 1145[14] | AD | |

| LGGS J004347.31+411203.6 | 1143[5] | L/Teff | W Galaktyce Andromedy |

| LGGS J004047.22+404445.5 | 1140[4]–1379[5] | L/Teff | W Galaktyce Andromedy |

| LGGS J004035.08+404522.3 | 1140[4]–1354[5] | L/Teff | W Galaktyce Andromedy |

| LGGS J013343.30+303318.9 | 1139[5] | L/Teff | W Galaktyce Trójkąta |

| LGGS J003942.92+402051.1 | 1133[5] | L/Teff | W Galaktyce Andromedy |

| LGGS J004124.80+411634.7 | 1130[4]–1423[5] | L/Teff | W Galaktyce Andromedy |

| LGGS J013233.77+302718.8 | 1129[29] | L/Teff | W Galaktyce Trójkąta |

| HV 2781 (WOH S470) | 1129[21] | L/Teff | W Wielkim Obłoku Magellana |

| RSGC1-F02 | 1128[22] | L/Teff | W gromadzie otwartej RSGC1 |

| SMC 56389 (PMMR 148) | 1128[21] | L/Teff | W Małym Obłoku Magellana |

| LGGS J013454.31+304109.8 | 1122[5] | L/Teff | W Galaktyce Trójkąta |

| LGGS J004731.12+422749.1 | 1121[5] | L/Teff | W Galaktyce Andromedy |

| LGGS J004451.76+420006.0 | 1116[5] | L/Teff | W Galaktyce Andromedy |

| LGGS J013400.91+303414.9 | 1115[5] | L/Teff | W Galaktyce Trójkąta |

| ST Cephei | 1109[14] | AD | |

| HV 2561(LMC 141430) | 1107[21] | L/Teff | W Wielkim Obłoku Magellana |

| LGGS J004219.25+405116.4 | 1103[5] | L/Teff | W Galaktyce Andromedy |

| HD 102115 | 1100[14] | AD | |

| LGGS J004107.11+411635.6 | 1100[4]–1207[5] | L/Teff | W Galaktyce Andromedy |

| LGGS J004253.25+411613.9 | 1099[5] | L/Teff | W Galaktyce Andromedy |

| LGGS J004124.81+411206.1 | 1094[5] | L/Teff | W Galaktyce Andromedy |

| LGGS J004415.76+411750.7 | 1084[5] | L/Teff | W Galaktyce Andromedy |

| LGGS J004447.74+413050.0 | 1083[5] | L/Teff | W Galaktyce Andromedy |

| LGGS J013416.89+305158.3 | 1081[5] | L/Teff | W Galaktyce Trójkąta |

| LGGS J004031.00+404311.1 | 1080[4]–1383[5] | L/Teff | W Galaktyce Andromedy |

| SMC 49478 (PMMR 115) | 1077[21] | L/Teff | W Małym Obłoku Magellana |

| V366 Andromedae | 1076[14] | AD | |

| LGGS J003943.89+402104.6 | 1076[5] | L/Teff | W Galaktyce Andromedy |

| Trumpler 27-1 | 1073[31] | L/Teff | W prawdopodobnej masywnej gromadzie otwartej Trumpler 27 |

| LGGS J013336.64+303532.3 | 1073[5] | L/Teff | W Galaktyce Trójkąta |

| HV 897 (WOH S161) | 1073[21] | L/Teff | W Wielkim Obłoku Magellana |

| SMC 20133 (PMMR 41) | 1072[21] | L/Teff | W Małym Obłoku Magellana |

| LMC 174714 | 1072[21] | L/Teff | W Wielkim Obłoku Magellana |

| LGGS J013326.90+310054.2 | 1071[5] | L/Teff | W Galaktyce Trójkąta |

| LGGS J004531.13+414825.7 | 1070[4]–1420[5] | L/Teff | W Galaktyce Andromedy |

| IM Cassiopeiae | 1068[14] | AD | |

| HV 11262 (PMMR 16) | 1067[21] | L/Teff | W Małym Obłoku Magellana |

| Orbita Jowisza | 1064–1173 | Dla porównania | |

| LGGS J003811.56+402358.2 | 1060[5] | L/Teff | W Galaktyce Andromedy |

| LGGS J004030.64+404246.2 | 1060[5] | L/Teff | W Galaktyce Andromedy |

| HR 5171 Aa (V766 Centauri Aa) | 1060–1160[32] | L/Teff | |

| LGGS J004631.49+421133.1 | 1060[5] | L/Teff | W Galaktyce Andromedy |

| LGGS J003942.42+403204.1 | 1057[5] | L/Teff | W Galaktyce Andromedy |

| LGGS J004346.18+411515.0 | 1057[5] | L/Teff | W Galaktyce Andromedy |

| LGGS J004638.17+420008.9 | 1056[5] | L/Teff | W Galaktyce Andromedy |

| LGGS J004501.30+413922.5 | 1054[5] | L/Teff | W Galaktyce Andromedy |

| SMC 25879 (PMMR 54) | 1053[21] | L/Teff | W Małym Obłoku Magellana |

| LGGS J013416.28+303353.5 | 1048[5] | L/Teff | W Galaktyce Trójkąta |

| SU Persei | 1048[14] | AD | |

| LGGS J013322.82+301910.9 | 1048[5] | L/Teff | W Galaktyce Trójkąta |

| RSGC1-F05 | 1047[3] | L/Teff | W gromadzie otwartej RSGC1 |

| LGGS J013328.85+310041.7 | 1046[5] | L/Teff | W Galaktyce Trójkąta |

| WX Piscium | 1044[33] | L/Teff | |

| WOH G371 (LMC 146126) | 1043[21] | L/Teff | W Wielkim Obłoku Magellana |

| WOH S327 (LMC 142202) | 1043[21] | L/Teff | W Wielkim Obłoku Magellana |

| V358 Cassiopeiae | 1043[34] | AD | Czerwony hiperolbrzym w gwiazdozbiorze Kasjopei[35] |

| LGGS J003910.56+402545.6 | 1042[5] | L/Teff | W Galaktyce Andromedy |

| LGGS J004114.18+403759.8 | 1040[4]–1249[5] | L/Teff | W Galaktyce Andromedy |

| LGGS J003912.77+404412.1 | 1037[5] | L/Teff | W Galaktyce Andromedy |

| LGGS J004507.90+413427.4 | 1034[5] | L/Teff | W Galaktyce Andromedy |

| LGGS J004406.60+411536.6 | 1033[5] | L/Teff | W Galaktyce Andromedy |

| IRAS 04509-6922 | 1027[36] | L/Teff | W Wielkim Obłoku Magellana |

| AS Cephei | 1026[14] | AD | |

| LGGS J004120.25+403838.1 | 1021[5] | L/Teff | W Galaktyce Andromedy |

| LGGS J004108.42+410655.3 | 1021[5] | L/Teff | W Galaktyce Andromedy |

| LGGS J004125.72+411212.7 | 1020[4]–1359[5] | L/Teff | W Galaktyce Andromedy |

| LGGS J004059.50+404542.6 | 1020[4]–1367[5] | L/Teff | W Galaktyce Andromedy |

| LGGS J004607.45+414544.6 | 1018[5] | L/Teff | W Galaktyce Andromedy |

| HD 167861 | 1016[14] | AD | |

| LGGS J004305.77+410742.5 | 1015[5] | L/Teff | W Galaktyce Andromedy |

| LGGS J004424.94+412322.3 | 1013[5] | L/Teff | W Galaktyce Andromedy |

| HV 986 (WOH S368) | 1010[37] | L/Teff | W Wielkim Obłoku Magellana |

| LGGS J004415.17+415640.6 | 1008[5] | L/Teff | W Galaktyce Andromedy |

| LGGS J004118.29+404940.3 | 1005[5] | L/Teff | W Galaktyce Andromedy |

| Wybrane gwiazdy o promieniu mniejszym niż 1000 promieni Słońca, dla porównania | |||

| CZ Hydrae | 986[38] | L/Teff | Jedna z najchłodniejszych gwiazd, o temperaturze 2000 K[38] |

| Gwiazda Granat (Mi Cephei) | 972 ± 228[39] | L/Teff | Gwiazda zmienna półregularna, jedna z najczerwieńszych na niebie. Na podstawie średnicy kątowej jej rozmiar oceniano nawet na 1650 R☉[40] |

| V602 Carinae | 932[31]–1151[14] | AD | |

| Betelgeza (Alfa Orionis) | 764+116−62[41] | AD | Najjaśniejszy czerwony nadolbrzym na ziemskim niebie |

| Antares (Alfa Scorpii A) | 707[14] | AD | Starsze, zawyżone oceny rozmiaru zapewne wynikały z asymetrii atmosfery gwiazdy[42] |

| V354 Cephei | 685[31] | AD | |

| HV 2112 | 675-1193 | Kandydat na Obiekt Thorne-Żytkow | |

| Ro Cassiopeiae | 636-981 | Żółty hiperolbrzym, jeden z najrzadszych rodzajów gwiazd | |

| 119 Tauri (CE Tauri) | 587–593[43] (–608[44]) | AD | Zakrywana przez Księżyc, co pozwala na dokładne wyznaczenie średnicy kątowej |

| V382 Carinae (x Carinae) | 485 ± 40[45] | AD | Żółty hiperolbrzym, jeden z najrzadszych rodzajów gwiazd |

| La Superba (Y Canum Venaticorum) | 422 | Jedna z najchłodniejszych gwiazd, gwiazda węglowa | |

| Gwiazda Pistolet | 306[46]-420[47] | Błękitny hiperolbrzym o masie od 27 mas Słońca do 90 mas największego składnika Układu Słonecznego | |

| V509 Cassiopeiae | 400–900[48] | AD | Żółty hiperolbrzym, jeden z najrzadszych rodzajów gwiazd |

| V1427 Aquilae | 400–450[32] | DSKE | V1427 Aquilae może być żółtym hiperolbrzymem lub mniej jasną gwiazdą |

| CW Leonis | 390[49]–826[50] | L/Teff | Najjaśniejsza na niebie gwiazda węglowa |

| Wewnętrzny skraj pasa planetoid | 380 | Dla porównania | |

| AH Scorpii | 360[31] | L/Teff | AH Sco zmienia jasność obserwowaną o prawie trzy wielkości gwiazdowe w zakresie widzialnym, a całkowitą jasność o ok. 20%. Zmiany promienia nie są dobrze określone, bo zmienia się także temperatura gwiazdy. |

| V1302 Aquilae | 357[51] | L/Teff | Żółty hiperolbrzym, który zwiększył temperaturę do zakresu spotykanego wśród gwiazd LBV. De Beck i in. (2010) obliczyli promień 1342 R☉ przy założeniu znacznie niższej temperatury[50]. |

| Mira A (Omicron Ceti) | 332–402[52] | AD | Prototypowa miryda. De Beck i in. (2010) obliczyli promień 541 R☉[50]. |

| VV Cephei A | 516[15]–1000[53] | EB | Silnie zdeformowana gwiazda w ciasnym układzie podwójnym, tracąca masę na rzecz drugiego składnika przynajmniej podczas części orbity. Starsze oceny promienia sięgały 1900 R☉[27] |

| R Doradus | 298[54] | AD | Pod względem rozmiarów kątowych druga co do wielkości gwiazda na niebie, po Słońcu |

| Orbita Marsa | 297-358 | Dla porównania | |

| Słońce jako czerwony olbrzym | 256[55] | W tej fazie Słońce pochłonie Merkurego, Wenus, a być może także Ziemię, chociaż promień jej orbity wzrośnie wraz z utratą 1/3 masy przez Słońce. Podczas „spalania” helu gwiazda skurczy się do 10 R☉, ale później ponownie zwiększy promień, stając się niestabilną gwiazdą AGB, po czym odrzuci zewnętrzne warstwy tworząc mgławicę planetarną[56][57]. Dla porównania | |

| AG Carinae | ~250 | Może mieć średnicę do 500 średnic Słońca, jest gwiazdą zmienną typu S Doradus | |

| Eta Carinae A | ~240[58] | Była uznawana za najmasywniejszą znaną gwiazdę, aż w 2005 roku stwierdzono, że jest to układ podwójny. W trakcie wielkiej erupcji w XIX wieku miała rozmiar około 1400 R☉[59], obecnie oblicza się jej promień na od 60 do 881 R☉[60]. | |

| Orbita Ziemi | 215 (211–219) | Dla porównania | |

| Deneb | 203 | Najjaśniejsza gwiazda w konstelacji Łabędzia | |

| Orbita Wenus | 154–157 | Dla porównania | |

| Sadr | 150 | Druga co do jasności gwiazda w konstelacji Łabędzia, nadolbrzym typu F | |

| Epsilon Aurigae A (Almaaz A) | 143–358[61] | AD | W 1970 spekulowano, że jest to największa gwiazda o promieniu 2000–3000 R☉[62], ale okazało się, że gwiazdę otacza rozległy dysk pyłowy |

| WR 102ka | 92[63] | AD | W centrum Mgławicy Piwonia, jedna z najjaśniejszych gwiazd Drogi Mlecznej |

| Rigel | 78.9 | Najjaśniejsza gwiazda w konstelacji Oriona, nadolbrzym typu B | |

| Kanopus (Alfa Carinae) | 71[64] | AD | Druga co do jasności gwiazda nocnego nieba |

| Orbita Merkurego | 66–100 | Dla porównania | |

| LBV 1806-20 | 46–145[65] | L/Teff | Była kandydatka na najjaśniejszą gwiazdę Drogi Mlecznej z jasnością szacowaną początkowo na 40 milionów L☉[66], obecnie na 2 miliony L☉[67][68]. |

| Aldebaran (Alfa Tauri) | 43,06[14] | AD | Czternasta co do jasności gwiazda na nocnym niebie |

| Polaris (Alfa Ursae Minoris) | 37,5[69] | AD | Północna Gwiazda Polarna |

| R136a1 | 28,8[70]–35,4[71] | AD | Najmasywniejsza i najjaśniejsza znana gwiazda (315 M☉; 8,71 miliona L☉), w Wielkim Obłoku Magellana. |

| Arktur (Alfa Boötis) | 24,25[14] | AD | Najjaśniejsza gwiazda północnej półkuli niebieskiej |

| HDE 226868 | 20–22[72] | Towarzyszka czarnej dziury Cygnus X-1. Czarna dziura jest około 500 000 razy mniejsza niż gwiazda | |

| Pollux | 9,06 | Najjaśniejsza gwiazda w konstelacji Bliźniąt, posiada planetę większą niż Jowisz | |

| Spica A | 7.47 | Najjaśniejsza gwiazda w konstelacji Panny | |

| Bellatrix | 5,75 | Trzecia co do jasności gwiazda w konstelacji Oriona | |

| Regulus A | 4,35 | Najjaśniejsza gwiazda w konstelacji Lwa | |

| Wega | 2,5 | Piąta co do jasności gwiazda na nocnym niebie | |

| Syriusz A | 1,71 | Najjaśniejsza gwiazda na nocnym niebie, główny składnik układu podwójnego | |

| Altair | 1,63 - 2,03 | Dwunasta co do jasności gwiazda na nocnym niebie | |

| Alpha Centauri A (Rigil Kentaurus) | 1,21 | Trzecia co do jasności gwiazda na nocnym niebie | |

| Słońce | 1 | Największy obiekt w Układzie Słonecznym (dla porównania) | |

Zobacz też

- gwiazdozbiór

- lista gwiazd w poszczególnych gwiazdozbiorach

- najjaśniejsze gwiazdy

- lista najzimniejszych gwiazd

- lista najgorętszych gwiazd

- lista gwiazd o najmniejszej masie

- lista najstarszych gwiazd

Uwagi

- ↑ Metody wyznaczenia promienia:

- AD: na podstawie średnicy kątowej i odległości

- L/Teff: na podstawie jasności bolometrycznej i temperatury efektywnej

- DSKE: na podstawie emisji z dysku

- EB: na podstawie obserwacji zaćmienia w układzie podwójnym.

Przypisy

- ↑ Emily M. Levesque, Philip Massey, K.A.G. Olsen, Bertrand Plez, Georges Meynet, Andre Maeder. The Effective Temperatures and Physical Properties of Magellanic Cloud Red Supergiants: The Effects of Metallicity. „Astrophysical Journal”. 645 (2). DOI: 10.1086/504417. arXiv:astro-ph/0603596. Bibcode: 2006ApJ...645.1102L.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Yi Ren, Bi-Wei Jiang, On the Granulation and Irregular Variation of Red Supergiants, „Astrophysical Journal”, 1, 898, 2020, s. 24, DOI: 10.3847/1538-4357/ab9c17, ISSN 1538-4357 (ang.).

- ↑ a b c d Thomas K.T. Fok, Jun-ichi Nakashima, Bosco H.K. Yung, Chih-Hao Hsia i inni. Maser Observations of Westerlund 1 and Comprehensive Considerations on Maser Properties of Red Supergiants Associated with Massive Clusters. „Astrophysical Journal”. 760 (1), s. 65, 2012. DOI: 10.1088/0004-637X/760/1/65. arXiv:1209.6427. Bibcode: 2012ApJ...760...65F (ang.).

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Philip Massey, Kate Anne Evans, The Red Supergiant Content of M31, „Astrophysical Journal”, 2, 826, 2016, s. 224, DOI: 10.3847/0004-637X/826/2/224, Bibcode: 2016ApJ...826..224M, arXiv:1605.07900.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au av aw ax ay az ba bb bc bd be bf bg bh bi bj bk bl bm bn bo bp bq br bs bt bu bv bw bx by bz ca cb Michael S. Gordon, Roberta M. Humphreys, Terry J. Jones. Luminous and Variable Stars in M31 and M33. III. The Yellow and Red Supergiants and Post-red Supergiant Evolution. „The Astrophysical Journal”. 825 (1), s. 50, 2016. DOI: 10.3847/0004-637X/825/1/50. ISSN 0004-637X (ang.).

- ↑ Yi Ren, B.W. Jiang, On Granulation and Irregular Variation of Red Supergiants, „arXiv [astro-ph]”, 2020, DOI: 10.3847/1538-4357/ab9c17, arXiv:2006.06605 [dostęp 2020-12-09].

- ↑ David A. Neufeld, Karl M. Menten, Carlos Durán, Rolf Güsten i inni. Terahertz Water Masers: II. Further SOFIA/GREAT Detections toward Circumstellar Outflows, and a Multitransition Analysis. „arXiv [astro-ph]”, 2020-11-03. arXiv:2011.01807 (ang.).

- ↑ Mikako Matsuura, J.A. Yates, M.J. Barlow, B. M. Swinyard i inni. Herschel SPIRE and PACS observations of the red supergiant VY CMa: analysis of the molecular line spectra. „Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society”. 437 (1), s. 532–546, 2013-10-30. DOI: 10.1093/mnras/stt1906. arXiv:1310.2947. ISSN 0035-8711 (ang.).

- ↑ a b c Roberta M. Humphreys, VY Canis Majoris: The Astrophysical Basis of Its Luminosity, „arXiv”, 2006, Bibcode: 2006astro.ph.10433H, arXiv:astro-ph/0610433 (ang.).

- ↑ Philip Massey, Emily M. Levesque, Bertrand Plez, Bringing VY Canis Majoris Down to Size: An Improved Determination of Its Effective Temperature, „Astrophysical Journal”, 2, 646, 2006, s. 1203–1208, DOI: 10.1086/505025, arXiv:astro-ph/0604253.

- ↑ J.D. Monnier i inni, High-Resolution Imaging of Dust Shells by Using Keck Aperture Masking and the IOTA Interferometer, „Astrophysical Journal”, 1, 605, 2004, s. 436–461, DOI: 10.1086/382218, Bibcode: 2004ApJ...605..436M, arXiv:astro-ph/0401363.

- ↑ Emma R Beasor, Ben Davies, B Arroyo-Torres, A Chiavassa i inni. The evolution of red supergiant mass-loss rates. „Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society”. 475 (1), s. 55, 2018. DOI: 10.1093/mnras/stx3174. arXiv:1712.01852. Bibcode: 2018MNRAS.475...55B (ang.).

- ↑ W.M Fawley, M Cohen, The open cluster NGC 7419 and its M7 supergiant IRC +60375, „Astrophysical Journal”, 193, 1974, s. 367, DOI: 10.1086/153171, Bibcode: 1974ApJ...193..367F.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q P. Cruzalèbes i inni, A catalogue of stellar diameters and fluxes for mid-infrared interferometry, „Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society”, 3, 490, 2019, s. 3158–3176, DOI: 10.1093/mnras/stz2803, Bibcode: 2019MNRAS.490.3158C, arXiv:1910.00542.

- ↑ a b Keivan G. Stassun i inni, The revised TESS Input Catalog and Candidate Target List, „The Astronomical Journal”, 4, 158, 2019, DOI: 10.3847/1538-3881/ab3467, Bibcode: 2019AJ....158..138S, arXiv:1905.10694.

- ↑ a b Steven R. Goldman, Jacco Th. van Loon, The wind speeds, dust content, and mass-loss rates of evolved AGB and RSG stars at varying metallicity, „Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society”, 1, 465, 2016, s. 403–433, DOI: 10.1093/mnras/stw2708, Bibcode: 2017MNRAS.465..403G, arXiv:1610.05761.

- ↑ Martin A.T. Groenewegen, Greg C. Sloan, Luminosities and mass-loss rates of Local Group AGB stars and Red Supergiants, „Astronomy & Astrophysics”, 609, 2018, A114, DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/201731089, ISSN 0004-6361, arXiv:1711.07803 [dostęp 2020-12-09].

- ↑ a b B. Arroyo-Torres i inni, The atmospheric structure and fundamental parameters of the red supergiants AH Scorpii, UY Scuti, and KW Sagittarii, „Astronomy & Astrophysics”, 554, 2013, A76, DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/201220920.

- ↑ B. Zhang i inni, The distance and size of the red hypergiant NML Cygni from VLBA and VLA astrometry, „Astronomy & Astrophysics”, 544, 2012, A42, DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/201219587, ISSN 0004-6361 [dostęp 2020-12-09] (ang.).

- ↑ E. De Beck i inni, Probing the mass-loss history of AGB and red supergiant stars from CO rotational line profiles - II. CO line survey of evolved stars: derivation of mass-loss rate formulae, „Astronomy & Astrophysics”, 523, 2010, A18, DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/200913771, ISSN 0004-6361, arXiv:1008.1083 [dostęp 2020-12-09].

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Brooke Dicenzo, Emily M. Levesque, Atomic Absorption Line Diagnostics for the Physical Properties of Red Supergiants, „The Astronomical Journal”, 4, 157, 2019, DOI: 10.3847/1538-3881/ab01cb, Bibcode: 2019AJ....157..167D, arXiv:1902.01862.

- ↑ a b Roberta M. Humphreys i inni, Exploring the Mass Loss Histories of the Red Supergiants, „arXiv e-prints”, 2020, DOI: 10.3847/1538-3881/abab15, Bibcode: 2020AJ....160..145H, arXiv:2008.01108 (ang.).

- ↑ D. Kamath, P.R. Wood, H. Van Winckel. Optically visible post-AGB stars, post-RGB stars and young stellar objects in the Large Magellanic Cloud. „Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society”. 454 (2), s. 1468–1502, 2015. DOI: 10.1093/mnras/stv1202. arXiv:1508.00670. Bibcode: 2015MNRAS.454.1468K (ang.).

- ↑ a b c Martin A.T. Groenewegen, Greg C. Sloan, Luminosities and mass-loss rates of Local Group AGB stars and Red Supergiants, „Astronomy & Astrophysics”, 609, 2018, A114, DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/201731089, ISSN 0004-6361, arXiv:1711.07803.

- ↑ Mikako Matsuura, B. Sargent, Bruce Swinyard, Jeremy Yates i inni. The mass-loss rates of red supergiants at low metallicity: Detection of rotational CO emission from two red supergiants in the Large Magellanic Cloud. „Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society”. 462 (3), s. 2995, 2016. DOI: 10.1093/mnras/stw1853. arXiv:1608.01729. Bibcode: 2016MNRAS.462.2995M (ang.).

- ↑ Ryan P. Norris: Seeing Stars Like Never Before: A Long-term Interferometric Imaging Survey of Red Supergiants (ang.). Georgia State University, 2019.

- ↑ a b Tabela 4 w Emily M. Levesque i inni, The Effective Temperature Scale of Galactic Red Supergiants: Cool, but Not as Cool as We Thought, „Astrophysical Journal”, 2, 628, 2005, s. 973–985, DOI: 10.1086/430901, Bibcode: 2005ApJ...628..973L, arXiv:astro-ph/0504337.

- ↑ C. De Jager, H. Nieuwenhuijzen, K.A. Van Der Hucht, Mass loss rates in the Hertzsprung-Russell diagram, „Astronomy and Astrophysics Supplement Series”, 72, 1988, s. 259, ISSN 0365-0138, Bibcode: 1988A&AS...72..259D.

- ↑ a b Maria R. Drout, Philip Massey, Georges Meynet, The yellow and red supergiants of M33, „Astrophysical Journal”, 2, 750, 2012, s. 97, DOI: 10.1088/0004-637X/750/2/97, arXiv:1203.0247.

- ↑ Aura Arévalo, The Red Supergiants in the Supermassive Stellar Cluster Westerlund 1, 2019, DOI: 10.11606/D.14.2019.tde-12092018-161841 (ang.).

- ↑ a b c d M. Messineo, A.G.A. Brown, A Catalog of Known Galactic K-M Stars of Class I Candidate Red Supergiants in Gaia DR2, „The Astronomical Journal”, 1, 158, 2019, s. 20, DOI: 10.3847/1538-3881/ab1cbd, Bibcode: 2019AJ....158...20M, arXiv:1905.03744.

- ↑ a b A.M. van Genderen i inni, Pulsations, eruptions, and evolution of four żółty hiperolbrzyms, „Astronomy and Astrophysics”, 631, 2019, A48, DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/201834358, Bibcode: 2019A&A...631A..48V, arXiv:1910.02460.

- ↑ F. L Schöier i inni, The abundance of HCN in circumstellar envelopes of AGB stars of different chemical type, „Astronomy & Astrophysics”, 550, 2013, A78, DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/201220400, Bibcode: 2013A&A...550A..78S, arXiv:1301.2129.

- ↑ L. Bourgés i inni, The JMMC Stellar Diameters Catalog v2 (JSDC): A New Release Based on SearchCal Improvements, „Astronomical Data Analysis Software and Systems XXIII”, 485, 2014, s. 223, ISSN 1050-3390, Bibcode: 2014ASPC..485..223B (ang.).

- ↑ I. McDonald, A.A. Zijlstra, M.L. Boyer, Fundamental Parameters and Infrared Excesses of Hipparcos Stars, „Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society”, 1, 427, 2012, s. 343–57, DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2966.2012.21873.x, Bibcode: 2012MNRAS.427..343M, arXiv:1208.2037.

- ↑ Steve Goldman: The metallicity dependence of maser emission and mass loss from red supergiants and asymptotic giant branch star (ang.). Keele University, 2017.

- ↑ https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1086/520797/pdf.

- ↑ a b Emelie Siderud: Dust emission modelling of AGB stars. 2020. (ang.)

- ↑ M. Montargès, W. Homan, D. Keller, N. Clementel i inni. NOEMA maps the CO J = 2 − 1 environment of the red supergiant μ Cep. „Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society”. 485 (2), s. 2417–2430, 2019. DOI: 10.1093/mnras/stz397. arXiv:1903.07129. Bibcode: 2019MNRAS.485.2417M (ang.).

- ↑ Jim Kaler: GARNET STAR (Mu Cephei) (ang.). STARS. [dostęp 2020-12-05].

- ↑ Meridith Joyce, Shing-Chi Leung, László Molnár, Michael Ireland i inni. Standing on the Shoulders of Giants: New Mass and Distance Estimates for Betelgeuse through Combined Evolutionary, Asteroseismic, and Hydrodynamic Simulations with MESA. „The Astrophysical Journal”. 902 (1), s. 63, 2020. DOI: 10.3847/1538-4357/abb8db. arXiv:2006.09837. Bibcode: 2020ApJ...902...63J (ang.).

- ↑ K. Ohnaka, K.-H. Hofmann, D. Schertl, G. Weigelt i inni. High spectral resolution imaging of the dynamical atmosphere of the red supergiant Antares in the CO first overtone lines with VLTI/AMBER. „Astronomy & Astrophysics”. 555, s. A24, 2013. DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/201321063. arXiv:1304.4800. Bibcode: 2013A&A...555A..24O (ang.).

- ↑ M. Montargès i inni, The convective photosphere of the red supergiant CE Tau. I. VLTI/PIONIER H-band interferometric imaging, „Astronomy & Astrophysics”, 12, 614, 2018, A12, DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/201731471, Bibcode: 2018A&A...614A..12M, arXiv:1802.06086.

- ↑ Greg Parker, The second reddest star in the sky – 119 Tauri, CE Tauri, New Forest Observatory, 2 lipca 2012 [dostęp 2019-01-04] [zarchiwizowane z adresu 2018-08-25].

- ↑ M.A.T. Groenewegen, Analysing the spectral energy distributions of Galactic classical Cepheids, „Astronomy and Astrophysics”, 635, 2020, DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/201937060, Bibcode: 2020A&A...635A..33G, arXiv:2002.02186.

- ↑ F. Najarro i inni, Metallicity in the Galactic Center: The Quintuplet Cluster, „Astrophysical Journal”, 2, 691, 2009, s. 1816–1827, DOI: 10.1088/0004-637X/691/2/1816, Bibcode: 2009ApJ...691.1816N, arXiv:0809.3185.

- ↑ R.M. Lau i inni, Nature Versus Nurture: Luminous Blue Variable Nebulae in and Near Massive Stellar Clusters at the Galactic Center, „The Astrophysical Journal”, 785 (2), 2014, s. 120, DOI: 10.1088/0004-637X/785/2/120, Bibcode: 2014ApJ...785..120L, arXiv:1403.5298.

- ↑ H. Nieuwenhuijzen i inni, The hypergiant HR 8752 evolving through the yellow evolutionary void, „Astronomy & Astrophysics”, 546, 2012, A105, DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/201117166, Bibcode: 2012A&A...546A.105N.

- ↑ A.B. Men’shchikov1 i inni, Structure and physical properties of the rapidly evolving dusty envelope of IRC +10216 reconstructed by detailed two-dimensional radiative transfer modeling, „Astronomy and Astrophysics”, 3, 392, 2001, s. 921–929, DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361:20020954, Bibcode: 2002A&A...392..921M, arXiv:astro-ph/0206410.

- ↑ a b c E. De Beck i inni, Probing the mass-loss history of AGB and red supergiant stars from CO rotational line profiles. II. CO line survey of evolved stars: Derivation of mass-loss rate formulae, „Astronomy and Astrophysics”, 523, 2010, A18, DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/200913771, Bibcode: 2010A&A...523A..18D, arXiv:1008.1083.

- ↑ Dinh-V.-Trung i inni, Probing the Mass-Loss History of the żółty hiperolbrzym IRC+10420, „Astrophysical Journal”, 1, 697, 2009, s. 409–419, DOI: 10.1088/0004-637X/697/1/409, Bibcode: 2009ApJ...697..409D, arXiv:0903.3714.

- ↑ H.C. Woodruff i inni, Interferometric observations of the Mira star o Ceti with the VLTI/VINCI instrument in the near-infrared, „Astronomy & Astrophysics”, 2, 421, 2004, s. 703–714, DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361:20035826, Bibcode: 2004A&A...421..703W, arXiv:astro-ph/0404248.

- ↑ E. Pollmann i inni, Periodic Hα Emission in the Eclipsing Binary VV Cephei, „Information Bulletin on Variable Stars”, 2018, DOI: 10.22444/IBVS.6249, Bibcode: 2018IBVS.6249....1P.

- ↑ Keiichi Ohnaka, Gerd Weigelt, Karl-Heinz Hofmann, Infrared Interferometric Three-dimensional Diagnosis of the Atmospheric Dynamics of the AGB Star R Dor with VLTI/AMBER, „Astrophysical Journal”, 1, 883, 2019, s. 89, DOI: 10.3847/1538-4357/ab3d2a, Bibcode: 2019ApJ...883...89O, arXiv:1908.06997.

- ↑ K.R. Rybicki, C. Denis, On the Final Destiny of the Earth and the Solar System, „Icarus”, 1, 151, 2001, s. 130–137, DOI: 10.1006/icar.2001.6591, Bibcode: 2001Icar..151..130R.

- ↑ K.-P. Schröder, R. Connon Smith, Distant future of the Sun and Earth revisited, „Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society”, 1, 386, 2008, s. 155–163, DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2966.2008.13022.x, Bibcode: 2008MNRAS.386..155S, arXiv:0801.4031.

- ↑ E. Vassiliadis, P.R. Wood, Evolution of low- and intermediate-mass stars to the end of the asymptotic giant branch with mass loss, „Astrophysical Journal”, 413, 1993, s. 641, DOI: 10.1086/173033, Bibcode: 1993ApJ...413..641V.

- ↑ T.R. Gull, A. Damineli, JD13 – Eta Carinae in the Context of the Most Massive Stars, „Proceedings of the International Astronomical Union”, 5, 2010, s. 373–398, DOI: 10.1017/S1743921310009890, Bibcode: 2010HiA....15..373G, arXiv:0910.3158.

- ↑ Nathan Smith, Explosions triggered by violent binary-star collisions: Application to Eta Carinae and other eruptive transients, „Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society”, 3, 415, 2011, s. 2020–2024, DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2966.2011.18607.x, Bibcode: 2011MNRAS.415.2020S, arXiv:1010.3770.

- ↑ D. John Hillier i inni, On the Nature of the Central Source in η Carinae, „The Astrophysical Journal”, 837, 553, 2001, s. 837, DOI: 10.1086/320948, Bibcode: 2001ApJ...553..837H.

- ↑ B.K. Kloppenborg i inni, Interferometry of ɛ Aurigae: Characterization of the Asymmetric Eclipsing Disk, „The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series”, 1, 220, 2015, s. 14, DOI: 10.1088/0067-0049/220/1/14, Bibcode: 2015ApJS..220...14K, arXiv:1508.01909.

- ↑ Ask Andy: The Biggest Star, „Ottawa Citizen”, 1970, s. 23.

- ↑ A. Barniske, L.M. Oskinova, W. -R. Hamann, Two extremely luminous WN stars in the Galactic center with circumstellar emission from dust and gas, „Astronomy and Astrophysics”, 3, 486, 2008, s. 971, DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361:200809568, Bibcode: 2008A&A...486..971B, arXiv:0807.2476.

- ↑ P. Cruzalebes i inni, Fundamental parameters of 16 late-type stars derived from their angular diameter measured with VLTI/AMBER, „Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society”, 1, 434, 2013, s. 437–450, DOI: 10.1093/mnras/stt1037, Bibcode: 2013MNRAS.434..437C, arXiv:1306.3288.

- ↑ S.S. Eikenberry i inni, Infrared Observations of the Candidate LBV 1806-20 and Nearby Cluster Stars, „Astrophysical Journal”, 1, 616, 2004, s. 506–518, DOI: 10.1086/422180, Bibcode: 2004ApJ...616..506E, arXiv:astro-ph/0404435.

- ↑ Meghan Kennedy, LBV 1806-20 AB?, SolStation [dostęp 2017-10-28] [zarchiwizowane z adresu 2017-11-13].

- ↑ D.F. Figer, F. Najarro, R.P. Kudritzki, The Double-lined Spectrum of LBV 1806-20, „Astrophysical Journal”, 2, 610, 2004, L109–L112, DOI: 10.1086/423306, Bibcode: 2004ApJ...610L.109F, arXiv:astro-ph/0406316.

- ↑ Y. Nazé, G. Rauw, D. Hutsemékers, The first X-ray survey of Galactic luminous blue variables, „Astronomy & Astrophysics”, 47, 538, 2012, A47, DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/201118040, Bibcode: 2012A&A...538A..47N, arXiv:1111.6375.

- ↑ Y.A. Fadeyev, Evolutionary status of Polaris, „Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society”, 1, 449, 2015, s. 1011–1017, DOI: 10.1093/mnras/stv412, Bibcode: 2015MNRAS.449.1011F, arXiv:1502.06463.

- ↑ R. Hainich i inni, The Wolf–Rayet stars in the Large Magellanic Cloud, „Astronomy & Astrophysics”, 27, 565, 2014, A27, DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/201322696, Bibcode: 2014A&A...565A..27H, arXiv:1401.5474.

- ↑ P.A. Crowther i inni, The R136 star cluster hosts several stars whose individual masses greatly exceed the accepted 150 M⊙ stellar mass limit, „Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society”, 2, 408, 2010, s. 731–751, DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2966.2010.17167.x, Bibcode: 2010MNRAS.408..731C, arXiv:1007.3284.

- ↑ J. Ziółkowski, Evolutionary constraints on the masses of the components of HDE 226868/Cyg X-1 binary system, „Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society”, 3, 358, 2005, s. 851–859, DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2966.2005.08796.x, Bibcode: 2005MNRAS.358..851Z, arXiv:astro-ph/0501102. Note: For radius, see Table 1 with d=2 kpc.

Linki zewnętrzne

- Three largest stars identified, BBC News. Science, 11 stycznia 2005 [dostęp 2020-12-07] (ang.).

- John Moll, Hiperolbrzym UY Scuti jest największą znaną nam gwiazdą, tylkoastronomia.pl, 10 lutego 2015 [dostęp 2020-12-07].

- Największa obecnie znana gwiazda: Stephenson 2-18, Astrofan, 15 listopada 2020 [dostęp 2020-12-07].

Media użyte na tej stronie

Autor: Faren29, Licencja: CC BY-SA 4.0

Size comparison of evolved red supergiant star Stephenson 2-18, extreme red hypergiant star VY Canis Majoris and luminous red supergiant star UY Scuti.

Autor: Dave Jarvis (https://dave.autonoma.ca/), Licencja: CC BY-SA 3.0

Relative sizes of the planets in the solar system and several well known stars. Star colours are estimated (based on temperature) and Saturn's rings are shown slightly larger in the picture than to scale. Blender 3D was used for the models, lighting, and rendering. The GIMP was used to assemble and label the six renders into a single image. Wolfram Alpha was used to calculate each star's base colour through Wien's Law. The relative sizes of stars in terms of their representative solar radius were calculated for all stars in each frame. Texture maps for stars were created using images of the Sun from SOHO. Planetary texture and bump maps (excluding Earth) were from Celestia Motherlode. Lastly, Earth's texture and bump map were obtained from Natural Earth III.