Metoda Schulzego

Metoda Schulzego (ang.: Schulze method, Schwartz Sequential Dropping (SSD), Cloneproof Schwartz Sequential Dropping (CSSD), Beatpath Method, Beatpath Winner, Path Voting, Path Winner) – metoda wyborcza, czyli oddawania i liczenia głosów, stworzona w 1997 przez Markusa Schulzego w celu wybierania jednego zwycięzcy w głosowaniu preferencyjnym.

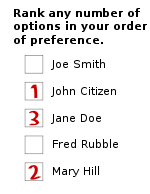

Głosowanie odbywa się przez wpisanie liczby przy każdym kandydacie. Wyborca oddaje głos, oznaczając wybranych kandydatów numerami: zaznaczając '1' obok najbardziej preferowanego kandydata, '2' obok następnego w kolejności preferencji itd.

Metoda ta może zostać użyta także w celu wyłonienia listy zwycięzców.

Jeżeli w zestawieniach kandydatów parami, w wyniku tych zestawień jeden z nich jest preferowany, metoda Schulzego gwarantuje, że ten kandydat wygra wybory. Dzięki tej właściwości metoda Schulzego z racji definicji jest metodą Condorceta[1].

Jako pierwszy metody wyłaniania zwycięzcy wyborczego na zasadzie oddawania głosu jako uszeregowanych preferencji opracował już w XVIII wieku francuski matematyk Jean Condorcet. Rajmund Lullus, średniowieczny filozof z Majorki, zaproponował podobne metody[2] już w XIII wieku, przy czym swoje obliczenia wykonywał iteratywnie (parami, po kolei), budując przy tym maszyny logiczne. Z kolei ok. r. 1670 niemiecki matematyk Gottfried Leibniz zastosował metody Lullusa do liczenia, nadając im nazwę ars combinatorica, tworząc przy okazji rodzaj kodu binarnego. Z tego powodu Lull jest dziś uważany za ojca informatyki, a w jego metodach ustalono zapożyczenia z matematyki afrykańskiej[3][4].

Metoda Schulzego stała się najbardziej rozpowszechnioną metodą Condorceta. Obecnie jest ona używana przez szereg organizacji, w tym: Wikimedia, Debian, Gentoo i Software in the Public Interest.

Szereg rozmaitych strategii heurystycznych zostało zaproponowanych przez informatyków w celu sprawnego obliczenia wyniku wyborów zgodnie z metodą Schulzego. Najważniejsze z nich to tzw. ścieżkowa (ang. path heuristic) i zbioru Schwartza (ang. Schwartz set heuristic), opisane poniżej. Wszystkie strategie stosujące heurystykę obliczają tego samego zwycięzcę i różnią się od siebie tylko detalami algorytmu.

Strategia ścieżkowa (path heuristic)

W zastosowaniu metody Schulzego (jak i innych ordynacjach preferencyjnych wyłaniającego jednego wygrywającego (ang. single-winner election methods), każdy formularz do oddawania głosu zawiera kompletny spis wszystkich biorących udział w wyborach kandydatów. Wyborca ustawia ich według preferencji, oznaczając wybranych kandydatów numerami (zaznaczając '1' obok najbardziej preferowanego kandydata, '2' obok następnego w kolejności preferencji itd.).

Wyborca może przypisać tę samą preferencję wielu kandydatom, jak i nie oznaczyć kandydata. Jeżeli wyborca nie oznaczy kandydata, znaczy to, że ściśle preferuje oznaczonych nad nieoznaczonym i że nie preferuje nikogo wśród nieoznaczonych.

Rys matematyczny

Gdzie d[V,W] stanowi liczbę wyborców, którzy ściśle preferują kandydata V nad kandydata W:

Ścieżka prowadząca od kandydata X do kandydata Y o mocy p to ciąg kandydatów C(1),...,C(n) o następujących właściwościach:

- C(1) = X i C(n) = Y.

- Dla wszystkich i = 1,...,(n-1): d[C(i),C(i+1)] > d[C(i+1),C(i)].

- Dla wszystkich i = 1,...,(n-1): d[C(i),C(i+1)] ≥ p.

- Istnieje i, 1 ≤ i ≤ n-1 takie że: d[C(i),C(i+1)] = p.

p[A,B], moc najsilniejszej ścieżki od kandydata A do kandydata B, to wartość maksymalna wśród ścieżek od kandydata A do kandydata B. Jeżeli w ogóle nie istnieje ścieżka od kandydata A do kandydata B, wtedy p[A,B] : = 0.

Kandydat D jest lepszym od kandydata E, wtedy i tylko wtedy, gdy p[D,E] > p[E,D].

Kandydat D jest potencjalnie zwycięzcą (wygrywającym) wtedy i tylko wtedy, gdy p[D,E] ≥ p[E,D] dla każdego innego kandydata E.

Pseudokod

Zakładając C jako liczbę kandydatów biorących udział w wyborach, moce najsilniejszych ścieżek można obliczyć algorytmem Floyda-Warshalla. Poniższy pseudokod realizuje ten algorytm iteratywnie, od 1 do C. Jest to dokładne obliczenie, bez przybliżeń. Zdefiniowane ścieżki zaistniały jeszcze przed przeprowadzeniem tych obliczeń.

- Wejście: d[i,j] stanowi liczbę wyborców, którzy ściśle preferują kandydata i nad kandydata j.

- Wyjście: Kandydat i stanowi potencjalnego zwycięzcę wtedy i tylko wtedy, gdy „zwycięzca[i] = prawda”.

1 od i : = 1 do C

2 od j : = 1 do C

3 jeżeli i ≠ j wtedy

4 jeżeli d[i,j] > d[j,i] wtedy

5 p[i,j] := d[i,j]

6 w przeciwnym wypadku

7 p[i,j] := 0

8

9 od i : = 1 do C

10 od j : = 1 do C

11 jeżeli i ≠ j wtedy

12 od k : = 1 do C

13 jeżeli i ≠ k oraz j ≠ k wtedy

14 p[j,k] : = max { p[j,k]; min { p[j,i]; p[i,k] } }

15

16 od i : = 1 do C

17 zwycięzca[i] := prawda

18 od j : = 1 do C

19 jeżeli i ≠ j oraz p[j,i] > p[i,j] wtedy

20 zwycięzca[i] := fałsz

Przykłady

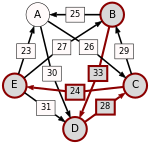

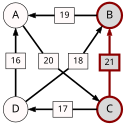

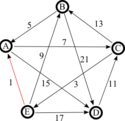

Przykład 1

45 wyborców wybiera spośród 5 kandydatów:

- 5 ACBED (oznacza: pięciu wyborców wybrało preferencyjnie: A > C > B > E > D)

- 5 ADECB

- 8 BEDAC

- 3 CABED

- 7 CAEBD

- 2 CBADE

- 7 DCEBA

- 8 EBADC

- 5 ADECB

| d[*,A] | d[*,B] | d[*,C] | d[*,D] | d[*,E] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| d[A,*] | 20 | 26 | 30 | 22 | |

| d[B,*] | 25 | 16 | 33 | 18 | |

| d[C,*] | 19 | 29 | 17 | 24 | |

| d[D,*] | 15 | 12 | 28 | 14 | |

| d[E,*] | 23 | 27 | 21 | 31 |

Krytyczne przegrane wśród najsilniejszych ścieżek (ang. strongest paths) są tu pogrubione.

| ... do A | ... do B | ... do C | ... do D | ... do E | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| od A ... | A-(30)-D-(28)-C-(29)-B | A-(30)-D-(28)-C | A-(30)-D | A-(30)-D-(28)-C-(24)-E | |

| od B ... | B-(25)-A | B-(33)-D-(28)-C | B-(33)-D | B-(33)-D-(28)-C-(24)-E | |

| od C ... | C-(29)-B-(25)-A | C-(29)-B | C-(29)-B-(33)-D | C-(24)-E | |

| od D ... | D-(28)-C-(29)-B-(25)-A | D-(28)-C-(29)-B | D-(28)-C | D-(28)-C-(24)-E | |

| od E ... | E-(31)-D-(28)-C-(29)-B-(25)-A | E-(31)-D-(28)-C-(29)-B | E-(31)-D-(28)-C | E-(31)-D |

| p[*,A] | p[*,B] | p[*,C] | p[*,D] | p[*,E] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p[A,*] | 28 | 28 | 30 | 24 | |

| p[B,*] | 25 | 28 | 33 | 24 | |

| p[C,*] | 25 | 29 | 29 | 24 | |

| p[D,*] | 25 | 28 | 28 | 24 | |

| p[E,*] | 25 | 28 | 28 | 31 |

Kandydat E jest potencjalnym wygrywającym, ponieważ p[E,X] ≥ p[X,E] dla każdego innego kandydata X.

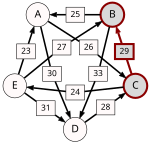

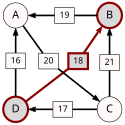

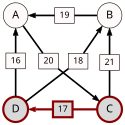

Przykład 2

30 wyborców wybiera spośród 4 kandydatów:

- 5 ACBD

- 2 ACDB

- 3 ADCB

- 4 BACD

- 3 CBDA

- 3 CDBA

- 1 DACB

- 5 DBAC

- 4 DCBA

- 2 ACDB

| d[*,A] | d[*,B] | d[*,C] | d[*,D] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| d[A,*] | 11 | 20 | 14 | |

| d[B,*] | 19 | 9 | 12 | |

| d[C,*] | 10 | 21 | 17 | |

| d[D,*] | 16 | 18 | 13 |

Krytyczne przegrane wśród najsilniejszych ścieżek (ang. strongest paths) są tu pogrubione.

| ... do A | ... do B | ... do C | ... do D | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| od A ... | A-(20)-C-(21)-B | A-(20)-C | A-(20)-C-(17)-D | |

| od B ... | B-(19)-A | B-(19)-A-(20)-C | B-(19)-A-(20)-C-(17)-D | |

| od C ... | C-(21)-B-(19)-A | C-(21)-B | C-(17)-D | |

| od D ... | D-(18)-B-(19)-A | D-(18)-B | D-(18)-B-(19)-A-(20)-C |

| p[*,A] | p[*,B] | p[*,C] | p[*,D] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| p[A,*] | 20 | 20 | 17 | |

| p[B,*] | 19 | 19 | 17 | |

| p[C,*] | 19 | 21 | 17 | |

| p[D,*] | 18 | 18 | 18 |

Kandydat D jest potencjalnym wygrywającym, ponieważ p[D,X] ≥ p[X,D] dla każdego innego kandydata X.

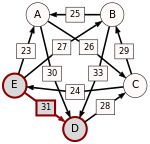

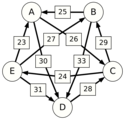

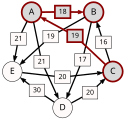

Przykład 3

30 wyborców wybiera spośród 5 kandydatów:

- 3 ABDEC

- 5 ADEBC

- 1 ADECB

- 2 BADEC

- 2 BDECA

- 4 CABDE

- 6 CBADE

- 2 DBECA

- 5 DECAB

- 5 ADEBC

| d[*,A] | d[*,B] | d[*,C] | d[*,D] | d[*,E] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| d[A,*] | 18 | 11 | 21 | 21 | |

| d[B,*] | 12 | 14 | 17 | 19 | |

| d[C,*] | 19 | 16 | 10 | 10 | |

| d[D,*] | 9 | 13 | 20 | 30 | |

| d[E,*] | 9 | 11 | 20 | 0 |

Krytyczne przegrane wśród najsilniejszych ścieżek (ang. strongest paths) są tu pogrubione.

| ... do A | ... do B | ... do C | ... do D | ... do E | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| od A ... | A-(18)-B | A-(21)-D-(20)-C | A-(21)-D | A-(21)-E | |

| od B ... | B-(19)-E-(20)-C-(19)-A | B-(19)-E-(20)-C | B-(19)-E-(20)-C-(19)-A-(21)-D | B-(19)-E | |

| od C ... | C-(19)-A | C-(19)-A-(18)-B | C-(19)-A-(21)-D | C-(19)-A-(21)-E | |

| od D ... | D-(20)-C-(19)-A | D-(20)-C-(19)-A-(18)-B | D-(20)-C | D-(30)-E | |

| od E ... | E-(20)-C-(19)-A | E-(20)-C-(19)-A-(18)-B | E-(20)-C | E-(20)-C-(19)-A-(21)-D |

| p[*,A] | p[*,B] | p[*,C] | p[*,D] | p[*,E] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p[A,*] | 18 | 20 | 21 | 21 | |

| p[B,*] | 19 | 19 | 19 | 19 | |

| p[C,*] | 19 | 18 | 19 | 19 | |

| p[D,*] | 19 | 18 | 20 | 30 | |

| p[E,*] | 19 | 18 | 20 | 19 |

Kandydat B jest potencjalnym wygrywającym, ponieważ p[B,X] ≥ p[X,B] dla każdego innego kandydata X.

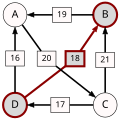

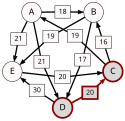

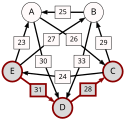

Przykład 4

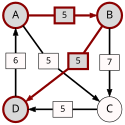

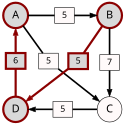

9 wyborców wybiera spośród 4 kandydatów:

- 3 ABCD

- 2 DABC

- 2 DBCA

- 2 CBDA

- 2 DABC

| d[*,A] | d[*,B] | d[*,C] | d[*,D] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| d[A,*] | 5 | 5 | 3 | |

| d[B,*] | 4 | 7 | 5 | |

| d[C,*] | 4 | 2 | 5 | |

| d[D,*] | 6 | 4 | 4 |

Krytyczne przegrane wśród najsilniejszych ścieżek (ang. strongest paths) są tu pogrubione.

| ... do A | ... do B | ... do C | ... do D | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| od A ... | A-(5)-B | A-(5)-C | A-(5)-B-(5)-D | |

| od B ... | B-(5)-D-(6)-A | B-(7)-C | B-(5)-D | |

| od C ... | C-(5)-D-(6)-A | C-(5)-D-(6)-A-(5)-B | C-(5)-D | |

| od D ... | D-(6)-A | D-(6)-A-(5)-B | D-(6)-A-(5)-C |

| p[*,A] | p[*,B] | p[*,C] | p[*,D] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| p[A,*] | 5 | 5 | 5 | |

| p[B,*] | 5 | 7 | 5 | |

| p[C,*] | 5 | 5 | 5 | |

| p[D,*] | 6 | 5 | 5 |

Kandydat B i kandydat D są potencjalnymi wygrywającymi, ponieważ p[B,X] ≥ p[X,B] dla każdego innego kandydata X, jak i p[D,Y] ≥ p[Y,D] dla każdego innego kandydata Y.

Strategia zbioru Schwartza (Schwartz set heuristic)

Zbiór Schwartza

Definicja zbioru Schwartza, według zastosowania w metodzie Schulzego to:

- Zbiór niepokonanych jest zbiorem kandydatów, z których żaden nie przegrał z nikim poza zbiorem.

- Skrajnie wewnętrzny zbiór niepokonanych to zbiór niepokonanych, który nie zawiera w sobie podzbioru stanowiącego zbiór niepokonanych.

- Zbiór Schwartza jest zbiorem kandydatów, którzy należą do skrajnie wewnętrznych zbiorów niepokonanych.

Rys matematyczny

Wyborcy głosują przez wykonanie preferencyjnego rankingu kandydatów, jak w każdym innym głosowaniu metodą Condorceta.

Metoda Schulzego stosuje zestawianie kandydatów parami według Condorceta, w następstwie czego wybierany jest zwycięzca każdego takiego zestawienia.

Następnie, metoda Schulzego postępuje algorytmicznie w następujący sposób: w celu wybrania jednego zwycięzcy (lub w celu otrzymania rankingu):

- Oblicz zbiór Schwartza przez spisanie wszystkich (bez opuszczania) przegranych.

- Jeżeli nie zaistnieje przegrana pośród elementów tego zbioru, wtedy element ten wygrywa lub elementy te (w liczbie mnogiej, w wypadku remisu) wygrywają, i na tym kończy się obliczenie.

- W przeciwnym przypadku opuść (ang. drop) najsłabszą przegraną (lub przegrane, w przypadku remisowych przegranych: ex æquo) zaistniałą w zestawieniu pomiędzy dwoma elementami tego zbioru. Wykonaj ponownie polecenie nr 1.

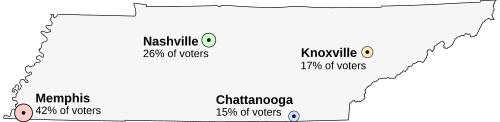

Przykład z wyborem stolicy Tennessee

Sytuacja

Oto przykład fikcyjnego wyboru stolicy stanu Tennessee spośród kilku miast-kandydatów. Populacja tego stanu jest skoncentrowana głównie wokół jego czterech największych miast, które rozrzucone są na mapie stanu. W tym fikcyjnym przypadku wszyscy mieszkańcy stanu zamieszkują te miasta i pragną mieszkać jak najbliżej stolicy.

Kandydatami na stolicę są:

- Memphis, największe miasto stanu, gdzie mieszka 42% wyborców, lecz ulokowane jest daleko od pozostałych miast.

- Nashville, gdzie mieszka 26% wyborców.

- Knoxville, gdzie mieszka 17% wyborców.

- Chattanooga, gdzie mieszka 15% wyborców.

Preferencje tych wyborców ułożyłyby się mianowicie:

| 42% wyborców (blisko Memphis) | 26% wyborców (blisko Nashville) | 15% wyborców (blisko Chattanooga) | 17% wyborców (blisko Knoxville) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

Rezultat zastosowania metody Schulzego przedstawiony jako tablica:

| A | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Memphis | Nashville | Chattanooga | Knoxville | ||

| B | Memphis | [A] 58% [B] 42% | [A] 58% [B] 42% | [A] 58% [B] 42% | |

| Nashville | [A] 42% [B] 58% | [A] 32% [B] 68% | [A] 32% [B] 68% | ||

| Chattanooga | [A] 42% [B] 58% | [A] 68% [B] 32% | [A] 17% [B] 83% | ||

| Knoxville | [A] 42% [B] 58% | [A] 68% [B] 32% | [A] 83% [B] 17% | ||

| Bilanse głosowania w zestawieniu kandydatów parami (wygrane-przegrane-remisy): | 0-3-0 | 3-0-0 | 2-1-0 | 1-2-0 | |

| Głosy przeciw w największych przegranych w parze: | 58% | N/A | 68% | 83% | |

- [A] przedstawia wyborców, którzy preferowali kandydata opisanego w kolumnie od kandydata opisanego rzędowo

- [B] przedstawia wyborców, którzy preferowali kandydata opisanego rzędowo od kandydata opisanego w kolumnie

Wygrani z poszczególnych zestawień par

Na początek, spisane tu zostały wszystkie możliwe pary, ze wskazaniem kandydata wygrywającego w tychże parach:

| Para | Zwycięzca w parze |

|---|---|

| Memphis (42%) vs. Nashville (58%) | Nashville 58% |

| Memphis (42%) vs. Chattanooga (58%) | Chattanooga 58% |

| Memphis (42%) vs. Knoxville (58%) | Knoxville 58% |

| Nashville (68%) vs. Chattanooga (32%) | Nashville 68% |

| Nashville (68%) vs. Knoxville (32%) | Nashville 68% |

| Chattanooga (83%) vs. Knoxville (17%) | Chattanooga: 83% |

Można tu użyć albo liczby oddanych głosów, albo procentowe zestawienia ułamka oddanych głosów; wybór tu jest bez znaczenia.

Opuszczanie (dropping)

Następnie, oto spis miast-kandydatów, z bilansem dla każdego z nich (wygrane-przegrane)

- Nashville 3-0

- Chattanooga 2-1

- Knoxville 1-2

- Memphis 0-3

Zbiorem Schwartza jest tu zbiór jednoelementowy zawierający Nashville, jako że Nashville bije wszystkie inne miasta wynikiem trzy do zera. Na tej podstawie, Nashville wygrywa wybory.

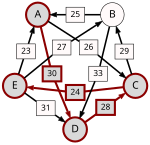

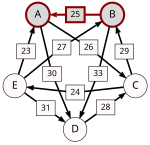

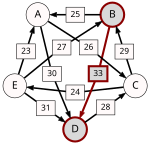

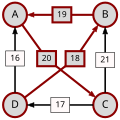

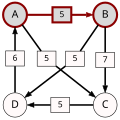

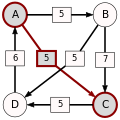

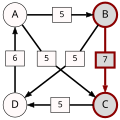

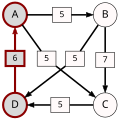

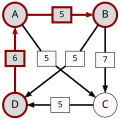

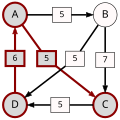

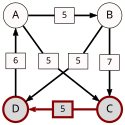

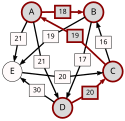

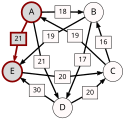

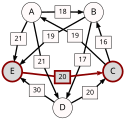

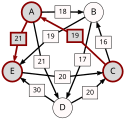

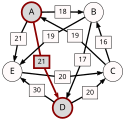

Przykład z niejednoznacznością

Dajmy na to, że zaistniała niejednoznaczność co do popularności kandydatów: A, B, C, i D.

- A > B 68%

- C > A 52%

- A > D 62%

- B > C 72%

- B > D 84%

- C > D 91%

W tej sytuacji, zbiór Schwartza zawiera A, B i C, ponieważ każdy z nich bije kandydaturę D.

- A > B 68%

- B > C 72%

- C > A 52%

Zgodnie z metodą Schulzego, opuszczamy (ang. drop) najmniejszą zaistniałą różnicę, toteż pozbywamy się: C > A i zostaje nam:

- A > B 68%

- B > C 72%

Nowy zbiór Schwartza to zbiór zawierający tylko A, jako że żadne miasto spoza tego zbioru nie bije A. Po tym obliczeniu A, jako element zbioru jednoelementowego, wygrywa wybory.

Podsumowanie

W powyższym (pierwszym) przykładzie wyborów metodą Schulzego, zwyciężyło miasto-kandydat Nashville. Taki wynik jest zagwarantowany metodą Condorceta[1]. W przypadku zastosowania ordynacji proporcjonalnej lub innej metody, Memphis wygrałoby jako miasto mające największą populację, pomimo tego, że Nashville wygrywa każde zestawienie w symulowanych wyborach przeprowadzonych wśród par miast. Nashville wygrywa także przy zastosowaniu metody Bordy. Za to metoda natychmiastowej dogrywki[5] w tym przypadku wskazałaby na stolicę miasto-kandydata Knoxville, pomimo tego, że więcej wyborców preferowało Nashville nad Knoxville.

Kryteria spełnione i niespełnione

Kryteria spełnione

Metoda Schulzego spełnia następujące kryteria:

- Uniwersalność

- Suwerenność

- Brak dyktatury

- Kryterium Pareta[6]

- Kryterium monotoniczności[7]

- Kryterium większości wyborczej

- Kryterium Condorceta

- Przegrany według kryterium Condorceta

- Kryterium Smitha

- Kryterium Schwartza

- Lokalna niezależność nieistotnych alternatyw[8]

- Kryterium wzajemnych większości[9]

- Kryterium independence of clones[10][11]

- Kryterium reversal symmetry[12][13]

- Kryterium mono-append[14]

- Kryterium mono-add-plump[15]

- Kryterium resolvability[16][17]

- Algorytm wielomianowy[18]

Jeżeli wygrywające głosy według kryterium Condorceta są użyte jako definiujące daną moc przegrania wyborów, metoda ta również spełnia następujące dodatkowe kryteria:

Jeżeli różnice w wygranych w parach według Condorceta są użyte do zdefiniowania mocy przegrania wyborów, metoda ta również spełnia następujące dodatkowe kryterium:

- Kryterium uzupełniania symetrycznego[22] (ang. Symmetric-completion)

Kryteria niespełnione

Metoda Schulzego nie spełnia następujących kryteriów:

- Jakiekolwiek kryteria niewspółmierne z kryterium Condorceta (np. niezależność nieistotnych alternatyw, kryterium partycypacji[23][24], kryterium spójności[25], odporność na głosowanie taktyczne[26], kryterium later-no-harm[27].

Niezależność nieistotnych alternatyw

Metoda Schulzego nie spełnia kryterium niezależności nieistotnych alternatyw[28]. Natomiast, cechuje ją słabsza właściwość znana jako lokalna niezależność nieistotnych alternatyw[8].

Można tę właściwość wyrazić następująco: jeżeli jeden kandydat (X) wygrywa wybory, po czym nowa alternatywa (Y) jest dodana, X wygra rozszerzone wybory, o ile Y nie jest elementem zbioru Smitha. Lokalna niezależność nieistotnych alternatyw implikuje spełnienie kryterium Condorceta.

Porównanie z innymi metodami głosowań preferencyjnych w przypadku jednego wygrywającego

Porównanie metody Schulzego z innymi metodami ordynacji preferencyjnej, w przypadku zaistnienia tylko jednego zwycięzcy:

| Monotoniczność | Zwycięzca według kryterium Condorceta | Przegrany według kryterium Condorceta | Kryterium większości[29] | Kryterium wzajemnych większości[30] | ang. Independence of clones criterion | ang. Reversal symmetry | Algorytm wielomianowy | Kryterium partycypacji[23], Kryterium spójności[25] | |

| Schulze | Tak | Tak | Tak | Tak | Tak | Tak | Tak | Tak | Nie |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ang. Ranked Pairs | Tak | Tak | Tak | Tak | Tak | Tak | Tak | Tak | Nie |

| ang. Kemeny-Young method | Tak | Tak | Tak | Tak | Tak | Nie | Tak | Nie | Nie |

| ang. Minimax Condorcet | Tak | Tak | Nie | Tak | Nie | Nie | Nie | Tak | Nie |

| ang. Nanson's method | Nie | Tak | Tak | Tak | Tak | Nie | Tak | Tak | Nie |

| ang. Nanson's method, podtyp: Baldwin method | Nie | Tak | Tak | Tak | Tak | Nie | Nie | Tak | Nie |

| Metoda natychmiastowej dogrywki[5] | Nie | Nie | Tak | Tak | Tak | Tak | Nie | Tak | Nie |

| ang. Coombs' method | Nie | Nie | Tak | Tak | Tak | Nie | Nie | Tak | Nie |

| ang. Contingent vote | Nie | Nie | Tak | Tak | Nie | Nie | Nie | Tak | Nie |

| ang. Contingent vote, podtyp: Sri Lankan contingent vote | Nie | Nie | Nie | Tak | Nie | Nie | Nie | Tak | Nie |

| ang. Contingent vote, podtyp: Supplementary Vote | Nie | Nie | Nie | Tak | Nie | Nie | Nie | Tak | Nie |

| metoda Bordy | Tak | Nie | Tak | Nie | Nie | Nie | Tak | Tak | Tak |

| metoda Bucklina[31] | Tak | Nie | Nie | Tak | Tak | Nie | Nie | Tak | Nie |

| Ordynacja większościowa | Tak | Nie | Nie | Tak | Nie | Nie | Nie | Tak | Tak |

| ang. Anti-plurality voting | Tak | Nie | Nie | Nie | Nie | Nie | Nie | Tak | Tak |

Różnice zaistniałe pomiędzy metodą Schulzego i metodą znana po angielsku jako Ranked Pairs opisano w sekcji nr 9 artykułu autorstwa Markusa Schulzego „A New Monotonic, Clone-Independent, Reversal Symmetric, and Condorcet-Consistent Single-Winner Election Method (Part 1 of 5)”[32].

Historia metody Schulzego

Markus Schulze opracował tę metodę w 1997. Po raz pierwszy została naświetlona w forum publicznym (na liście mailingowej) w 1998[33] i w 2000[34]. W następnych latach metoda Schulzego została zaadaptowana w celach wyborczych przez m.in. Software in the Public Interest (2003)[35], Debian (2003)[36], UserLinux (2003), Gentoo (2005), TopCoder (2005) i Sender Policy Framework (2005). Pierwsze monografie na temat metody Schulzego napisali: Nicolaus Tideman (2006) i Stahl z Johnsonem (2007).

Zastosowanie metody Schulzego

Metoda Schulzego nie jest jeszcze stosowana w wyborach rządowych. Natomiast obecnie zaczyna cieszyć się uznaniem i poparciem szeregu organizacji publicznych i społecznych. Wśród organizacji użytkujących Metodę Schulzego są następujące:

- The Alma Mater Society of the University of British Columbia (AMS)[37] i Langara Students' Union (LSU)[38] stosują metodę Schulzego dla potrzeb określenia stopnia uzyskanego wsparcia w ankietach na zasadzie głosowania preferencyjengo.

- Annodex Association[39]

- Blitzed.org[40][41]

- BoardGameGeek[42]

- Codex Alpe Adria[43][44]

- County Highpointers[45][46]

- Debian[36][47]

- EnMasse (fora internetowe)[48]

- EuroBillTracker[49]

- Fair Trade Northwest[50]

- Free Software Foundation Latin America (FSFLA)[51]

- Gentoo Foundation[52]

- Strażnik Prywatności GNU[53]

- Kingman Hall[54]

- Kumoricon[55]

- Mathematical Knowledge Management Interest Group[56]

- Metalab[57]

- Music Television (MTV)[58]

- North Shore Cyclists[59][60]

- OpenCouchSurfing[61][62]

- Pittsburgh Ultimate[63][64]

- RPMrepo[65][66]

- Sender Policy Framework (SPF)[67]

- Software in the Public Interest (SPI)[35]

- Students for Free Culture[68]

- TopCoder[69]

- Wikimedia Foundation[70]

Wikimedia Foundation

Największymi wyborami przeprowadzonymi dotychczas (wrzesień 2008) metodą Schulzego były wybory do rady Wikimedia's Board of Trustees w czerwcu 2008[70]: o jeden mandat ubiegało się 15 kandydatów, wybieranych potencjalnie przez 26 000 uprawnionych wyborców; w praktyce zgłoszono 3019 formularzy (czyli oddano tyle głosów, licząc każdego wyborcę jako jeden głos).

Jako że Chen wygrał pod względem kryterium Condorceta, on został wybrany do rady. Ponadto zaistniał remis w wyborach o miejsca od 6. do 9. pomiędzy Heiskanen, Postlethwaite, Smith i Saintonge. Heiskanen wygrał w zestawieniu w parze z Postlethwaite; Postlethwaite z Smith; Smith z Saintonge; Saintonge z Heiskanen.

| TC | AB | SK | HC | AH | JH | RP | SS | RS | DR | CS | MB | KW | PW | GK | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ting Chen | 1086 | 1044 | 1108 | 1135 | 1151 | 1245 | 1190 | 1182 | 1248 | 1263 | 1306 | 1344 | 1354 | 1421 | |

| Alex Bakharev | 844 | 932 | 984 | 950 | 983 | 1052 | 1028 | 990 | 1054 | 1073 | 1109 | 1134 | 1173 | 1236 | |

| Samuel Klein | 836 | 910 | 911 | 924 | 983 | 980 | 971 | 941 | 967 | 1019 | 1069 | 1099 | 1126 | 1183 | |

| Harel Cain | 731 | 836 | 799 | 896 | 892 | 964 | 904 | 917 | 959 | 1007 | 1047 | 1075 | 1080 | 1160 | |

| Ad Huikeshoven | 674 | 781 | 764 | 806 | 832 | 901 | 868 | 848 | 920 | 934 | 987 | 1022 | 1030 | 1115 | |

| Jussi-Ville Heiskanen | 621 | 720 | 712 | 755 | 714 | 841 | 798 | 737 | 827 | 850 | 912 | 970 | 943 | 1057 | |

| Ryan Postlethwaite | 674 | 702 | 726 | 756 | 772 | 770 | 755 | 797 | 741 | 804 | 837 | 880 | 921 | 1027 | |

| Steve Smith | 650 | 694 | 654 | 712 | 729 | 750 | 744 | 778 | 734 | 796 | 840 | 876 | 884 | 1007 | |

| Ray Saintonge | 629 | 703 | 641 | 727 | 714 | 745 | 769 | 738 | 789 | 812 | 848 | 879 | 899 | 987 | |

| Dan Rosenthal | 595 | 654 | 609 | 660 | 691 | 724 | 707 | 699 | 711 | 721 | 780 | 844 | 858 | 960 | |

| Craig Spurrier | 473 | 537 | 498 | 530 | 571 | 583 | 587 | 577 | 578 | 600 | 646 | 721 | 695 | 845 | |

| Matthew Bisanz | 472 | 498 | 465 | 509 | 508 | 534 | 473 | 507 | 531 | 513 | 552 | 653 | 677 | 785 | |

| Kurt M. Weber | 505 | 535 | 528 | 547 | 588 | 581 | 553 | 573 | 588 | 566 | 595 | 634 | 679 | 787 | |

| Paul Williams | 380 | 420 | 410 | 435 | 439 | 464 | 426 | 466 | 470 | 471 | 429 | 521 | 566 | 754 | |

| Gregory Kohs | 411 | 412 | 434 | 471 | 461 | 471 | 468 | 461 | 467 | 472 | 491 | 523 | 513 | 541 |

Każda liczba przedstawia wyborców, którzy przypisali preferencję kandydatowi po lewej, wyższą od tej przypisanej przez nich kandydatowi wskazanego u góry tabeli. Liczba na zielono reprezentuje wygraną w parze przez kandydata wskazanego w tablicy w kolumnie po lewej. Liczba na czerwono reprezentuje przegraną przez kandydata wskazanego w kolumnie po lewej.

Przypisy

- ↑ a b Jean Condorcet (17 wrze 1743 – 28 mar 1794): ang. Condorcet method

- ↑ Christopher M. Kelty, Ramon Llull (1232-1316): Logic. Memory. Wacko., [w:] Anthropology 375/575: Abracadabra: Language and Memory in Science and Technology [online], Houston: Rice University, 17 marca 2003 [dostęp 2008-09-25] (ang.).

- ↑ Dr. Scott W. Williams, Professor of Mathematics: Mathematics of the African Diaspora. Department of Mathematics, The State University of New York at Buffalo, 1997-05-25. [dostęp 2009-07-02]. Cytat: "Most histories of mathematics devote only a few pages to Ancient Egypt and to northern Africa during the 'Middle Ages´. Generally they ignore the history of mathematics in Africa south of the Sahara and give the impression that this history either did not exist or, at least, is not knowable, traceable, or, stronger still, that there was no mathematics at all south of the Sahara. In history, to Europeans, even the Africanity of Egyptian mathematics is often denied or suffers eurocentric views of conceptions of both 'history' and of 'mathematics' form the basis of such views. Contrary to the popular view, one can neither racially or geographically separate Egyptian civilization from its black African roots." (ang.).

- ↑ Chapter 7 Numeric systems. W: Ron Eglash: African Fractals: Modern Computing and Indigenous Design. Rutgers University Press, 1999, s. 100-101. ISBN 0-8135-2614-0, ISBN 978-0-8135-2614-0. Cytat: "The strong similarity of both symbolic technique and semantic categories to what Europeans termed „geomancy” was first noted by Flacourt (1661), but it was not until Trautmann (1939) that a serious claim was made for a common source for this Arabic, European, West African, and East African divination technique.The commonality was confirmed in a detailed formal analysis by Jaulin (1966). But where did it originate?

Skinner (1980) provides a well-documented history of the diffusion evidence, from the first specific written record, a ninth century Jewish commentary by Aran ben Joseph, to its modern use in Aleister Crowley's Liber 777. The oldest Arabic documents (those of az-Zanti in the thirteenth century) claim the origin of geomancy (ilm al-raml, „the science of sand”) through the Egyptian god Idris (Hermes Trismegistus), and while we need not take that as anything more than a claim to antiquity, a Nilotic influence is not unreasonable. Budge (1961) attempts to connect the use of sand in ancient Egyptian rituals to African geomancy, but it is hard to see this as unique. Mathematically, however, geomancy is strikingly out of place in non-African systems.

Like other linguistic codes, number bases tend to have an extremely long historical persistence. Even under Platonic rationalism, the ancient Greeks held 10 to be the most sacred of all numbers; the Kabbalah's Ayin Sof emanates by 10 Sefirot; and the Christian west counts on its „Hindu-Arabic” decimal notation.In Africa, on the other hand, base two calculation was ubiquitous, even for multiplication and division. And it is here that we find the cultural connotations of doubling that ground the divination practice in its religious significance.

The implications of this trajectory -- from sub-Saharan Africa, to North Africa, to Europe -- are quite significant for the history of mathematics. Following the introduction of geomancy to Europe by Hugo of Santalla in twelfth century Spain, it was taken up with great interest by the pre-science mystics of those times -- alchemists, hermeticists, and Rosicrucians (figure 7.9). But these European geomancers -- Raymond Lull, Robert Fludd, de Peruchio, Henry de Pisis and others -- persistently replaced the deterministic aspects of the system with chance. By mounting the sixteen figures on a wheel and spinning it, they maintained their society's exclusion of any connections between determinism and unpredictability. The Africans, on the other hand, seem to have emphasized such connections. In chapter 10 we will explore one source of this difference: the African concept of a “trickster” god, one who is both deterministic and unpredictable.

On a video recording I made of the Bamana divination, I noticed that the practitioners had used a shortcut method in some demonstrations (this may have been a parting gift, as the video was shot on my last day). As first taught to me, when they count off the pairs of random dashes, they link them by drawing short curves.The shortcut method then links those curves with larger curves, and those below with even larger curves.This upside-down Cantor set shows that they are not simply applying mod 2 again and again in a mindless fashion.The self-similar physical structure of the shortcut method vividly illustrates a recursive process, and as a non-traditional invention (there is no record of its use elsewhere) it shows active mathematical practice. Other African divination practices can be linked to recursion as well; for example Devisch (1991) describes the Yaka diviners' „self-generative” initiation and uterine symbolism.

Before leaving divination, there is one more important connection to mathematical history. While Raymond Lull, like other European alchemists, created wheels with sixteen divination figures, his primary interest was in the combinatorial possibilities offered by base-2 divisions. Lull's work was closely examined by German mathematician Gottfried Leibniz, whose Dissertatio de arte combinatoria, published in 1666 when he was twenty, acknowledges Lull's work as a precursor. Further exploration led Leibniz to introduce a base-2 counting system, creating what we now call the binary code. While there were many other African influences in the lives of Lull and Leibniz, it is not far-fetched to see a historical path for base-2 calculation that begins with African divination, runs through the geomancy of European alchemists, and is finally translated into binary calculation, where it is now applied in every digital circuit from alarm clocks to supercomputers.

In a 1995 interview in Wired magazine, techno-pop musician Brian Eno claimed that the problem with computers is that „they don't have enough African in them” Eno was, no doubt, trying to be complimentary, saying that there is some intuitive quality that is a valuable attribute of African culture. But in doing so he obscured the cultural origins of digital computing and did an injustice to the very concept he was trying to convey.”. (ang.). - ↑ a b ang. instant-runoff voting

- ↑ Schulze1, sekcja 4.2

- ↑ Schulze1, sekcja 4.4

- ↑ a b ang. local independence of irrelevant alternatives

- ↑ ang. mutual majority criterion

- ↑ ang. ndependence of clones criterion

- ↑ Schulze1, section 4.5

- ↑ ang. reversal symmetry

- ↑ Schulze1, sekcja 4.3

- ↑ Mono-append (ang.)

- ↑ Mono-add-plump (ang.)

- ↑ ang. resolvability criterion

- ↑ Schulze1, sekcja 4.1

- ↑ Schulze1, sekcja 2.4

- ↑ ang. plurality criterion, podtyp Woodall's plurality criterion

- ↑ a b Schulze1, sekcja 6

- ↑ Kryterium Woodalla CDTT (ang.)

- ↑ Uzupełnianie symetryczne (ang.)

- ↑ a b ang. participation criterion

- ↑ Schulze1, section 3.7

- ↑ a b ang. consistency criterion

- ↑ ang. compromising i burying

- ↑ ang. later-no-harm criterion

- ↑ ang.'independence of irrelevant alternatives

- ↑ ang. majority criterion

- ↑ ang, mutual majority criterion

- ↑ ang. Bucklin voting

- ↑ A New Monotonic, Clone-Independent, Reversal Symmetric, and Condorcet-Consistent Single-Winner Election Method (Part 1 of 5). 2008-08-04. [dostęp 2008-09-28]. (ang.).

- ↑ Patrz:

- Mike Ossipoff, Party List P.S., VII 1998

- Markus Schulze, Tiebreakers, Subcycle Rules, VIII 1998

- Markus Schulze, Maybe Schulze is decisive, VIII 1998

- Norman Petry, Schulze Method - Simpler Definition, IX 1998

- Markus Schulze, Schulze Method, XI 1998

- ↑ Patrz:

- Anthony Towns, Disambiguation of 4.1.5, XI 2000

- Norman Petry, Constitutional voting, definition of cumulative preference, XII 2000

- ↑ a b Process for adding new board members, I 2003

- ↑ a b Constitutional Amendment: Condorcet/Clone Proof SSD Voting Method, VI 2003

- ↑ May-June 2008 Voter-Funded Media Contest at University of British Columbia

- ↑ Langara Students Union 2008 Voter-Funded Media Contest. [zarchiwizowane z tego adresu]. (ang.).

- ↑ Election of the Annodex Association committee for 2007. cs.cornell.edu. [zarchiwizowane z tego adresu (2016-03-03)]., II 2007

- ↑ Blitzed. (ang.).

- ↑ Condorcet method for admin voting. I 2005. (ang.).

- ↑ Patrz:

- ↑ Codex Alpe Adria. (ang.).

- ↑ Codex Alpe Adria Competitions. (ang.).

- ↑ County Highpointers. (ang.).

- ↑ Adam Helman, Family Affair Voting Scheme - Schulze Method

- ↑ Patrz:

- ↑ EnMasse Forums. Kanada.

- ↑ Patrz:

- Candidate cities for EBTM05, EuroBillTracker Forum, XII 2004

- Meeting location preferences, EuroBillTracker Forum, XII 2004

- Date for EBTM07 Berlin, EuroBillTracker Forum, I 2007

- Vote the date of the Summer EBTM08 in Ljubljana, EuroBillTracker Forum, I 2008

- ↑ Fair Trade Northwest. (patrz: artykuł XI sekcja 2 ichniejszych bylaws)

- ↑ FSFLA Voting Instructions (hiszp.); FSFLA Voting Instructions (port.)

- ↑ Patrz:

- Czarter Fundacji Gentoo Gentoo Foundation Charter.

- Aron Griffis, 2005 Gentoo Trustees Election Results, V 2005

- Lars Weiler, Gentoo Weekly Newsletter 23 V 2005

- Daniel Drake, Gentoo metastructure reform poll is open, VI 2005

- Grant Goodyear, Results now more official, IX 2006

- 2007 Gentoo Council Election Results. dev.gentoo.org. [zarchiwizowane z tego adresu (2012-02-06)].

- ↑ GnuPG Logo Vote. logo-contest.gnupg.org. [zarchiwizowane z tego adresu (2013-10-03)]., XI 2006

- ↑ Patrz:

- Ka-Ping Yee, Condorcet elections, III 2005

- Ka-Ping Yee, Kingman adopts Condorcet voting, IV 2005

- ↑ Patrz:

- ↑ Mathematical Knowledge Management Interest Group (MKM-IG)]. (MKM-IG stosuje metodę Condorceta z podwójnym opuszczaniem. To oznacza: stosowanie rankingu Schulzego i rankingu znanego po angielsku jako Ranked Pairs, gdzie obliczenia wskazują na najpopularniejszego kandydata spośród wskazancyh przez te dwa rankingi według uszeregowania względem kryterium Kemeny score.)

Patrz:- MKM-IG Charter. mkm-ig.org. [zarchiwizowane z tego adresu (2017-03-23)].

- Michael Kohlhase, MKM-IG Trustees Election Details & Ballot, XI 2004

- Andrew A. Adams, MKM-IG Trustees Election 2005, XII 2005

- Lionel Elie Mamane, Elections 2007: Ballot, VIII 2007

- ↑ Generalversammlung 2007/Wahlmodus (niem.), III 2007

- ↑ Benjamin Mako Hill, Voting Machinery for the Masses, VII 2008

- ↑ North Shore Cyclists (NSC). (ang.).

- ↑ Wybory organizacji North Shore Cyclists. nscyc.org. [zarchiwizowane z tego adresu (2013-11-05)]., Głosowanie na wybór designu koszulki drużynowej NSC, September 2007

- ↑ OpenCouchSurfing. (ang.).

- ↑ Thomas Goorden, CS community city ambassador elections on 19 II 2008 in Antwerp and ..., XI 2007

- ↑ Pittsburgh Ultimate. (ang.).

- ↑ 2006 Community for Pittsburgh Ultimate Board Election. cs.cornell.edu. [zarchiwizowane z tego adresu (2016-03-03)]., IX 2006

- ↑ RPMrepo. (ang.).

- ↑ LogoVoting. XII 2007. (ang.).

- ↑ Patrz:

- SPF Council Election Procedures. openspf.org. [zarchiwizowane z tego adresu (2016-10-08)].

- 2006 SPF Council Election. cs.cornell.edu. [zarchiwizowane z tego adresu (2016-03-03)]., I 2006

- 2007 SPF Council Election. cs.cornell.edu. [zarchiwizowane z tego adresu (2016-03-03)]., I 2007

- ↑ Bylaws of the Students for Free Culture, article V, section 1.1.1

- ↑ Patrz:

- 2006 TopCoder Open Logo Design Contest, XI 2005

- 2006 TopCoder Collegiate Challenge Logo Design Contest, VI 2006

- 2007 TopCoder High School Tournament Logo. studio.topcoder.com. [zarchiwizowane z tego adresu (2011-07-17)]., IX 2006

- 2007 TopCoder Arena Skin Contest. studio.topcoder.com. [zarchiwizowane z tego adresu (2011-07-17)]., XI 2006

- 2007 TopCoder Open Logo Contest. studio.topcoder.com. [zarchiwizowane z tego adresu (2011-07-17)]., I 2007

- 2007 TopCoder Open Web Design Contest. studio.topcoder.com. [zarchiwizowane z tego adresu (2011-07-17)]., I 2007

- 2007 TopCoder Collegiate Challenge T-Shirt Design Contest. studio.topcoder.com. [zarchiwizowane z tego adresu (2011-07-17)]., IX 2007

- 2008 TopCoder Open Logo Design Contest. studio.topcoder.com. [zarchiwizowane z tego adresu (2011-07-17)]., IX 2007

- 2008 TopCoder Open Web Site Design Contest. studio.topcoder.com. [zarchiwizowane z tego adresu (2011-07-17)]., X 2007

- 2008 TopCoder Open T-Shirt Design Contest. studio.topcoder.com. [zarchiwizowane z tego adresu (2011-07-17)]., III 2008

- ↑ a b Patrz:

- Jesse Plamondon-Willard, Board election to use preference voting, V 2008

- Mark Ryan, 2008 Wikimedia Board Election results, VI 2008

- 2008 Board Elections, VI 2008

Schulze1: Markus Schulze: "A New Monotonic, Clone-Independent, Reversal Symmetric, and Condorcet-Consistent Single-Winner Election Method" [dostęp=2008-09-21] (ang.)

Linki zewnętrzne

Uwaga: Metodę Schulzego w źródłach poniżej oddają takie skrótowce jak CSSD, SSD, czy terminy beatpath, path winner, itp.

Głównie odniesienia

- Markus Schulze: Proposed Statutory Rules for the Schulze Single-Winner Election Method (ang.)

- Markus Schulze: A New Monotonic and Clone-Independent Single-Winner Election Method (także tu: [1] i [2]) (ang.)

- Markus Schulze: A New Monotonic, Clone-Independent, Reversal Symmetric, and Condorcet-Consistent Single-Winner Election Method (ang.)

- Markus Schulze: Free Riding and Vote Management under Proportional Representation by the Single Transferable Vote (ang.)

- Markus Schulze: Implementing the Schulze STV Method (ang.)

- Markus Schulze: A New MMP Method (ang.)

- Markus Schulze: A New MMP Method (Part 2) (ang.)

Instrukcje (tutorials)

- Schulze-Methode, Uniwersytet w Stuttgarcie (niem.)

Argumenty za i przeciw

- Blake Cretney: [3] (ang.)

- James Green-Armytage: Voting Methods Survey (ang.)

- Rob LeGrand: Descriptions of ranked-ballot voting methods (ang.)

- Rob Loring: Accurate Democracy (ang.)

- Warren D. Smith: Schulze beatpaths method (ang.)

- Kevin Venzke: Election Methods and Criteria (ang.)

- Jochen Voss: The Debian Voting System

- election-methods: a mailing list containing technical discussions about election methods (ang.)

Artykuły w czasopismach naukowych

- Rosa Camps, Xavier Mora, and Laia Saumell: A Continuous Rating Method for Preferential Voting (ang.)

- Paul E. Johnson: Voting Systems (ang.)

- Tommi Meskanen and Hannu Nurmi: Distance from Consensus: a Theme and Variations (ang.)

- Tommi Meskanen and Hannu Nurmi: Analyzing Political Disagreement (ang.)

- Warren D. Smith : Descriptions of voting systems (ang.)

- Peter A. Taylor: Election Systems (ang.)

- Martin Wilke: Personalisierung der Verhältniswahl durch Varianten der Single Transferable Vote (niem.)

- Anbu Yue, Weiru Liu, and Anthony Hunter: Approaches to Constructing a Stratified Merged Knowledge Base (ang.)

Monografie i inne książki

- Saul Stahl and Paul E. Johnson: Understanding Modern Mathematics ISBN 0-7637-3401-2 (ang.)

- Nicolaus Tideman: Collective Decisions and Voting: The Potential for Public Choice [4], ISBN 0-7546-4717-X (ang.)

Oprogramowanie

- Blake Cretney: Voting Software Project

- Mathew Goldstein: Condorcet with Dual Dropping Perl Scripts (ang.)

- Eric Gorr: Condorcet Voting Calculator

- Benjamin Mako Hill: Selectricity and RubyVote (ang.)

- Thomas Hirsch: Java implementation of the Schulze method (ang.)

- Rob Lanphier: Electowidget

- Evan Martin: Haskell Condorcet Module (ang.)

- Andrew Myers: Condorcet Internet Voting Service (CIVS) (ang.)

- Brian Olson: BetterPolls.com (ang.)

- Jeffrey O’Neill: OpenSTV (ang.)

Przedsięwzięcia parlamentarne i wyborcze

- Arizonans for Condorcet Ranked Voting [5] (ang.)

- Arizona Competitive Elections Reform Act (Ustawa w stanie Arizona dot. reformy wyborczej) (ang.)

- Przewodnik dla wyborcy w stanie Arizona, USA, azvoterform.com (ang.)

- http://www.azcentral.com/members/Blog/PoliticalInsider/22368, azcentral.com (ang.)

- Felieton w East Velley Tribune, eastvalleytribune.com (ang.)

- "Arizona high school student files paperwork for initiatives for IRV and easeir ballot access", ballot-access.org (ang.)

Media użyte na tej stronie

Autor: Markus Schulze, Licencja: CC BY-SA 3.0

Another graphic to illustrate the Schulze method.

Autor: Markus Schulze, Licencja: CC BY-SA 3.0

Another graphic to illustrate the Schulze method.

Autor: Markus Schulze, Licencja: CC BY-SA 3.0

Another graphic to illustrate the Schulze method.

Autor: Markus Schulze, Licencja: CC BY-SA 3.0

Another graphic to illustrate the Schulze method.

Autor: Markus Schulze, Licencja: CC BY-SA 3.0

Another graphic to illustrate the Schulze method.

Autor: Ral315 and authors of software., Licencja: GPL

Voting software in 2008 Wikimedia Board of Trustee elections.

Autor: Markus Schulze, Licencja: CC BY-SA 3.0

Another graphic to illustrate the Schulze method.

Autor: Markus Schulze, Licencja: CC BY-SA 3.0

Another graphic to illustrate the Schulze method.

Autor: Markus Schulze, Licencja: CC BY-SA 3.0

Another graphic to illustrate the Schulze method.

Autor: Markus Schulze, Licencja: CC BY-SA 3.0

Another graphic to illustrate the Schulze method.

Autor: Markus Schulze, Licencja: CC BY-SA 3.0

Another graphic to illustrate the Schulze method.

Autor: Markus Schulze, Licencja: CC BY-SA 3.0

Another graphic to illustrate the Schulze method.

Autor: Markus Schulze, Licencja: CC BY-SA 3.0

Another graphic to illustrate the Schulze method.

Autor: Markus Schulze, Licencja: CC BY-SA 3.0

Another graphic to illustrate the Schulze method.

Autor: Markus Schulze, Licencja: CC BY-SA 3.0

Another graphic to illustrate the Schulze method.

Autor: Markus Schulze, Licencja: CC BY-SA 3.0

Another graphic to illustrate the Schulze method.

Autor: Markus Schulze, Licencja: CC BY-SA 3.0

Another graphic to illustrate the Schulze method.

Autor: Autor nie został podany w rozpoznawalny automatycznie sposób. Założono, że to HB (w oparciu o szablon praw autorskich)., Licencja: CC-BY-SA-3.0

Schulze methode - Cloneproof Schwartz Sequential Dropping (CSSD), step two

Autor: Markus Schulze, Licencja: CC BY-SA 3.0

Another graphic to illustrate the Schulze method.

Autor: Markus Schulze, Licencja: CC BY-SA 3.0

Another graphic to illustrate the Schulze method.

Autor: Markus Schulze, Licencja: CC BY-SA 3.0

Another graphic to illustrate the Schulze method.

Autor: Markus Schulze, Licencja: CC BY-SA 3.0

Another graphic to illustrate the Schulze method.

Autor: Markus Schulze, Licencja: CC BY-SA 3.0

Another graphic to illustrate the Schulze method.

Autor: Markus Schulze, Licencja: CC BY-SA 3.0

Another graphic to illustrate the Schulze method.

Autor: Markus Schulze, Licencja: CC BY-SA 3.0

Another graphic to illustrate the Schulze method.

Autor: Markus Schulze, Licencja: CC BY-SA 3.0

Another graphic to illustrate the Schulze method.

Autor: Markus Schulze, Licencja: CC BY-SA 3.0

Another graphic to illustrate the Schulze method.

Autor: Markus Schulze, Licencja: CC BY-SA 3.0

Another graphic to illustrate the Schulze method.

Autor: Markus Schulze, Licencja: CC BY-SA 3.0

Another graphic to illustrate the Schulze method.

Autor: Markus Schulze, Licencja: CC BY-SA 3.0

Another graphic to illustrate the Schulze method.

Autor: Markus Schulze, Licencja: CC BY-SA 3.0

Another graphic to illustrate the Schulze method.

(c) Rspeer z angielskojęzycznej Wikipedii, CC-BY-SA-3.0

Created by en:User:Rspeer using en:Inkscape. Modified by Mark.

Autor: Markus Schulze, Licencja: CC BY-SA 3.0

Another graphic to illustrate the Schulze method.

Autor: Markus Schulze, Licencja: CC BY-SA 3.0

Another graphic to illustrate the Schulze method.

Autor: Markus Schulze, Licencja: CC BY-SA 3.0

Another graphic to illustrate the Schulze method.

Autor: Markus Schulze, Licencja: CC BY-SA 3.0

Another graphic to illustrate the Schulze method.

Autor: Markus Schulze, Licencja: CC BY-SA 3.0

Another graphic to illustrate the Schulze method.

Autor: Markus Schulze, Licencja: CC BY-SA 3.0

Another graphic to illustrate the Schulze method.

Autor: Markus Schulze, Licencja: CC BY-SA 3.0

Another graphic to illustrate the Schulze method.

Autor: Markus Schulze, Licencja: CC BY-SA 3.0

Another graphic to illustrate the Schulze method.

Autor: Markus Schulze, Licencja: CC BY-SA 3.0

Another graphic to illustrate the Schulze method.

Autor: Markus Schulze, Licencja: CC BY-SA 3.0

Another graphic to illustrate the Schulze method.

Autor: Markus Schulze, Licencja: CC BY-SA 3.0

Another graphic to illustrate the Schulze method.

Autor: Markus Schulze, Licencja: CC BY-SA 3.0

Another graphic to illustrate the Schulze method.

Autor: Markus Schulze, Licencja: CC BY-SA 3.0

Another graphic to illustrate the Schulze method.

Autor: Markus Schulze, Licencja: CC BY-SA 3.0

Another graphic to illustrate the Schulze method.

Autor: Markus Schulze, Licencja: CC BY-SA 4.0

Another graphic to illustrate the Schulze method.

Autor: Markus Schulze, Licencja: CC BY-SA 3.0

Another graphic to illustrate the Schulze method.

Autor: Autor nie został podany w rozpoznawalny automatycznie sposób. Założono, że to HB (w oparciu o szablon praw autorskich)., Licencja: CC-BY-SA-3.0

Schulze methode - Cloneproof Schwartz Sequential Dropping (CSSD), step three

Autor: Markus Schulze, Licencja: CC BY-SA 3.0

Another graphic to illustrate the Schulze method.

Autor: Markus Schulze, Licencja: CC BY-SA 3.0

Another graphic to illustrate the Schulze method.

Autor: Markus Schulze, Licencja: CC BY-SA 3.0

Another graphic to illustrate the Schulze method.

Autor: Markus Schulze, Licencja: CC BY-SA 3.0

Another graphic to illustrate the Schulze method.

Autor: Markus Schulze, Licencja: CC BY-SA 3.0

Another graphic to illustrate the Schulze method.

Autor: Markus Schulze, Licencja: CC BY-SA 3.0

Another graphic to illustrate the Schulze method.

Autor: Markus Schulze, Licencja: CC BY-SA 3.0

Another graphic to illustrate the Schulze method.

Autor: Markus Schulze, Licencja: CC BY-SA 3.0

Another graphic to illustrate the Schulze method.

Autor: Markus Schulze, Licencja: CC BY-SA 3.0

Another graphic to illustrate the Schulze method.

Autor: Markus Schulze, Licencja: CC BY-SA 3.0

Another graphic to illustrate the Schulze method.

Autor: Markus Schulze, Licencja: CC BY-SA 3.0

Another graphic to illustrate the Schulze method.

Autor: Markus Schulze, Licencja: CC BY-SA 3.0

Another graphic to illustrate the Schulze method.

Autor: Markus Schulze, Licencja: CC BY-SA 3.0

Another graphic to illustrate the Schulze method.

Autor: Markus Schulze, Licencja: CC BY-SA 3.0

Another graphic to illustrate the Schulze method.

Autor: Markus Schulze, Licencja: CC BY-SA 3.0

Another graphic to illustrate the Schulze method.

Autor: Markus Schulze, Licencja: CC BY-SA 3.0

Another graphic to illustrate the Schulze method.

Autor: Markus Schulze, Licencja: CC BY-SA 3.0

Another graphic to illustrate the Schulze method.

Autor: Markus Schulze, Licencja: CC BY-SA 3.0

Another graphic to illustrate the Schulze method.

Autor:

Oryginalnym przesyłającym był Rspeer z angielskiej Wikipedii

Later versions were uploaded by Abeg92 at en.wikipedia., Licencja: CC BY-SA 2.0Created by en:User:Rspeer using Inkscape. Based on a state outline from the Libre Map Project, released as CC-by-SA 2.0.

Autor: Autor nie został podany w rozpoznawalny automatycznie sposób. Założono, że to HB (w oparciu o szablon praw autorskich)., Licencja: CC-BY-SA-3.0

Schulze methode - Cloneproof Schwartz Sequential Dropping (CSSD), step one

Autor: Markus Schulze, Licencja: CC BY-SA 3.0

Another graphic to illustrate the Schulze method.