Symbolika faszystowska

Faszyzm jest ruchem różnorodnym i występuje w wielu odmianach, szczególnie rozpowszechnionych w okresie międzywojennym. Jego zwolennicy w poszczególnych krajach posługują się więc różnoraką symboliką. Często nawiązuje ona do specyfiki historii danego narodu, wzorując się w przeważającej liczbie przypadków na symbolice faszystowskiej, przyjętej we Włoszech i Niemczech.

Faszystowskie Włochy

Symbolem faszyzmu w jego włoskim wcieleniu pod przywództwem Benito Mussoliniego był fasces (od którego ruch wziął swoją nazwę)[1]. Były to wiązki rózg (poza Rzymem z zatkniętym w nie toporem) noszone przez liktorów przed najwyższymi urzędnikami, symbol ich władzy. Topór symbolizował w nich władzę nad życiem i śmiercią.

Hitlerowskie Niemcy

Niemiecka odmiana faszyzmu, nazywana narodowym socjalizmem, przyjęła tradycyjny salut rzymski, jako sposób pozdrawiania się wewnątrz organizacji. Głównym symbolem nazizmu, popularnym i często używanym już od czasów starożytnych przez wiele kultur, była swastyka. Przez nazistów postrzegana była jako znak kultury aryjskiej, do której Niemcy mieli rzekomo należeć. Pomimo że swastyka przed zaadaptowaniem jej na potrzeby hitlerowskich Niemiec była popularnym symbolem[2], dziś najczęściej utożsamiana jest właśnie z narodowym socjalizmem.

Podobnie jak faszyzm włoski, nazizm zaadaptował elementy swojej spuścizny etnicznej, wykorzystując historyczne symbole w celu lepszego oddania charakteru swego nacjonalizmu. Na przełomie XIX i XX wieku austriacki mistyk i literat Guido von List[3] wywarł ogromny wpływ na Reichsführera SS Heinricha Himmlera, który wprowadził różnorodne starożytne germańskie symbole do wyposażenia SS, zwłaszcza stylizowane podwójne runy Sieg, które stały się symbolem całej formacji[4]. Innymi historycznymi symbolami używanymi przez niemieckie siły zbrojne w III Rzeszy były m.in. Wolfsangel[4] i Totenkopf („trupia głowa”)[5], których unowocześnionymi wersjami „ozdabiano” mundury i insygnia.

Inne kraje

W innych krajach również pojawiły się ruchy faszystowskie lub bardzo do nich zbliżone. Posługiwały się one własną symboliką, m.in.:

- Głównym symbolem Brytyjskiej Unii Faszystów pod przywództwem Sir Oswalda Mosleya była flaga nazywana Błyskawica i Koło[6][7], przyjęta w 1936 roku. Widniały na niej „błyskawica czynu” i „koło jedności”, które miały symbolizować wartości ważne dla przyszłego faszystowskiego Państwa Brytyjskiego[8]. Znak ten określany był przez oponentów Mosleya jako „Błyskawica w Garnku”. Uprzednio ruch ten używał jako symbolu złotego fascesu znajdującego się w środku czerwonego koła, umieszczonego na niebieskim tle[9].

- Austriacki Front Ojczyźniany (Vaterländische Front, partia Engelberta Dollfußa i Kurta Schuschnigga, uważanych przez niektórych badaczy za twórców tzw. austrofaszyzmu) używał symbolu biało-czerwonego krzyża nazywanego Kruckenkreuz[10][11].

- Uważany często za faszystowski grecki Reżim 4 sierpnia używał za swój znak podwójnego topora nazywanego Labrys bądź Pelekys. Uważany on był przez dyktatora, generała Ioannisa Metaxasa za najstarszy symbol cywilizacji helleńskiej[12].

- Symbolem węgierskich faszystów, członków Nyilaskeresztes Párt (Strzałokrzyżowców) był strzałokrzyż[13][14].

- Symbolem norweskiej partii faszystowskiej Nasjonal Samling był Krzyż Świętego Olafa[15].

- Rywale António de Oliveira Salazara z ruchu narodowosyndykalistycznego używali Krzyża Zakonu Rycerzy Chrystusa.

- Symbolem rumuńskiej Żelaznej Gwardii był potrójny krzyż, zazwyczaj czarny, mający oznaczać kraty więzienne i męczennictwo. Czasem nazywany był Krzyżem Michała Archanioła, uznawanego przez członków ruchu za swego patrona[16].

- Symbolem hiszpańskiej Falangi były strzały i jarzmo (uprząż), które były również symbolami katolickich monarchistów[17][18]. Każda ze strzał reprezentuje jedno z dawnych pięciu królestw Hiszpanii[19].

- Brazylijscy integraliści posługiwali się znakiem greckiej litery sigma znajdującej się w białym okręgu na zielonym tle[20][21].

Związki z neopogaństwem

W wielu przypadkach symbole łączone z ruchami faszystowskimi, ale wywodzące się z tradycji indoeuropejskiej (takie jak właśnie swastyka), używane są przez niefaszystowskie neopogańskie ruchy i organizacje, takie jak islandzki Ásatrú czy walijski Cadw. Niektóre germańskie neopogańskie grupy wyrażają sprzeciw wobec wykorzystywaniu ich symboli w celach politycznych, zwłaszcza przeciwko określaniu ich jako „faszystowskie”. Wytoczyły one nawet proces walczącej z antysemityzmem Lidze Przeciw Zniesławieniu (ADL), która na swojej stronie internetowej[22] przedstawiła symbole neopogańskie jako neonazistowskie.

Sytuacja prawna

Poniżej znajdują się wizerunki graficzne symboli, spośród których niektóre używane były przez narodowosocjalistyczny rząd III Rzeszy lub organizacje ściśle z nim związane, jak również przez partie, których działalność została w Niemczech zakazana na mocy wyroków Federalnego Trybunału Konstytucyjnego.

Używanie insygniów i oznaczeń organizacji (takich jak swastyka czy strzałokrzyż), których działalność jest w Niemczech zakazana, może być nielegalne również w takich krajach jak Polska, Austria, Węgry, Czechy, Francja, Brazylia i inne. W Polsce mówi o tym art. 256 kodeksu karnego (Dz.U. z 2022 r. poz. 1138), a w Niemczech – art. 86a kodeksu karnego (StGB).

Symbole

Flaga z rzymskim fascesem – symbolem włoskiego faszyzmu.

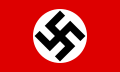

Flaga NSDAP (w latach 1935–1945 oficjalna flaga III Rzeszy) ze swastyką – symbolem niemieckiego nazizmu.

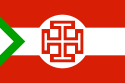

Flaga Frontu Ojczyźnianego z Kruckenkreuzem – symbolem austriackiego faszyzmu.

Flaga z Błyskawicą i Kołem – symbolem brytyjskich faszystów Oswalda Mosleya.

Historyczna flaga partii Fine Gael – symbol irlandzkiego faszyzującego – Ruchu Błękitnych Koszul.

Flaga z Jarzmem i strzałami – symbolem Falangi hiszpańskiej.

Flaga z godłem Narodowo-Socjalistycznego Ruchu Holenderskiego – ugrupowania holenderskich narodowych socjalistów.

Flaga z napisem „REX” – symbolem walońskich Reksistów.

Godło Nasjonal Samling z Krzyżem św. Olafa wpisany w tzw. krzyż słoneczny – symbolem norweskich faszystów Vidkuna Quislinga.

Flaga Narodowej Organizacji Młodzieżowej z labrysem – symbolem greckich faszystów.

Flaga z Krzyżem Michała Archanioła – symbolem rumuńskiej Żelaznej Gwardii.

Flaga Niezależnego Państwa Chorwackiego z literą '„U” – symbolem chorwackich ustaszów.

Flaga ze strzałokrzyżem – symbolem węgierskich Strzałokrzyżowców.

Flaga z symboliką czechosłowackiego ugrupowania faszyzującego – Vlajka

Flaga z sigmą – symbolem brazylijskiego integralizmu.

Flaga z błyskawicą – symbolem chilijskich narodowych socjalistów.

Flaga z falangą – symbolem Ruchu Narodowo-Radykalnego w Polsce

Zobacz też

- symbolika neonazistowska

- insygnia runiczne w III Rzeszy Niemieckiej

Przypisy

- ↑ Christopher Francese: Ancient Rome in So Many Words. Hippocrene Books, 2007, s. 123. ISBN 0-7818-1153-8.

- ↑ Juan Eduardo Cirlot, Jack Sage, Herbert Read: A dictionary of symbols. Routledge, 1993, s. 323. ISBN 0-415-03649-6.

- ↑ Richard S. Levy: Antisemitism: A Historical Encyclopedia of Prejudice and Persecution. ABC-CLIO, 2005, s. 425–426. ISBN 1-85109-439-3.

- ↑ a b Paul Hannon, Robin Lumsden: The Allgemeine-SS. Osprey Publishing, 1993, s. 18. ISBN 1-85532-358-3.

- ↑ Paul Hannon, Robin Lumsden: The Allgemeine-SS. Osprey Publishing, 1993, s. 15–16. ISBN 1-85532-358-3.

- ↑ Graham Macklin: Very Deeply Dyed in Black: sir Oswald Mosley and the Resurrection of British Fascism After 1945. I.B.Tauris, 2007, s. 17. ISBN 1-84511-284-9.

- ↑ David Stephen Lewis: Illusions of Grandeur: Mosley, Fascism, and British Society, 1931-81. Manchester University Press ND, 1987, s. 240. ISBN 0-7190-2354-8.

- ↑ Unities: Webster’s Quotations, Facts and Phrases. Icon Group International, Inc., s. 153. ISBN 0-546-67283-3.

- ↑ British Union of Fascists. [dostęp 2009-02-27]. (ang.).

- ↑ Günter Bischof, Anton Pelinka: The Americanization/westernization of Austria. Transaction Publishers, 2003, s. 268. ISBN 0-7658-0803-X.

- ↑ Barbara Jelavich: Modern Austria: Empire and Republic, 1815-1986. Cambridge University Press: 1987, s. 200. ISBN 0-521-31625-1.

- ↑ Believes: Webster’s Quotations, Facts and Phrases. Icon Group International, Inc., 2008, s. 455. ISBN 0-546-72190-7.

- ↑ Roger Griffin: The nature of Fascism. Routledge, 1993, s. 127. ISBN 0-415-09661-8.

- ↑ Carl C. Liungman: Thought Signs: The Semiotics of Symbols: Western Non-pictorial Ideograms. IOS Press, 1995, s. 324. ISBN 90-5199-197-5.

- ↑ Richard Landwehr: Frontfighters. Lulu.com, 2008, s. 26. ISBN 1-4357-5853-6.

- ↑ Romanian fascist parties. [dostęp 2009-02-27]. (ang.).

- ↑ Paola Bacchetta, Margaret Power: Right-wing Women: From Conservatives to Extremists Around the World. Routledge, 2002, s. 89. ISBN 0-415-92778-1.

- ↑ Arisotle A. Kallis: The Fascism Reader. Routledge, 2003, s. 230. ISBN 0-415-24359-9.

- ↑ Faith Berry, Richard Wright: Pagan Spain. Univ. Press of Mississippi, 1992, s. 55. ISBN 1-57806-427-9.

- ↑ Arthur Brakel, Boris Fausto: A Concise History of Brazil. Cambridge University Press, 1999, s. 209. ISBN 0-521-56526-X.

- ↑ Robert M. Levine: The History of Brazil. Greenwood Publishing Group, 1999, s. 103. ISBN 0-313-30390-8.

- ↑ ADL: Hate On Display: A Visual Database of Extremist Symbols, Logos and Tattoos. [dostęp 2009-02-27]. [zarchiwizowane z tego adresu (12 października 2007)]. (ang.).

Media użyte na tej stronie

Autor: F l a n k e r, Licencja: CC BY-SA 2.5

Łatwo można dodać ramkę naokoło tej grafiki

War flag of the Repubblica Sociale Italiana (the civil flag was the same of the present day Italian Republic, but was more rarely used in comparison with the war flag)

The flag of the Independent State of Croatia

Autor: Trimnapaschkan, Licencja: CC BY-SA 3.0

Party Flag of the Romanian fascist "Iron Guard" ("Legion of the Archangel Michael" or "Legionary Movement").

Autor: MesserWoland, Licencja: CC-BY-SA-3.0

Flag of the Hungarian fascist Arrow Cross Party.

Flag of the Spanish Falange of the Assemblies of the National Syndicalist Offensive

Autor: Mrmw, Licencja: CC0

Flag of National Socialist Movement

Flag of Fatherland Front of Austria

Autor: R-41, Licencja: CC BY-SA 3.0

Historical flag of the Fine Gael political party of the Republic of Ireland, (source here: [1]) It was flown alongside the tricolour flag of the the Republic of Ireland.(source here: [2]) The Fine Gael flag was previously historically used by its predecessor the Cumann na nGaedheal, and a faction within it, the quasi-fascist paramilitary group known as the Blueshirts. The symbol is the red Saint Patrick's Saltire defacing a dark blue background - dark blue is an Irish national colour.

Autor: Philly boy92, Licencja: CC BY-SA 3.0

The flag of the National Youth Organization of Greece.

Flag of the Rexist Party

Flag of the Fascist National Party (Partito Nazionale Fascista) from 1926 to 1943. There were variations of the flag with different styles of fasces, this image shows one of those styles. A variant of the flag can be seen flying atop of a building in the Italian film titled "L’Arrivo della Missione Nazionale Socialista inviata dal Fuerher...", Giornale Luce C0294 del 03/11/1942, shown here in a small version of the film at the Cincitta Luce website at 2:14 [1] in a large version via Youtube at 2:09: [2] Colour and design has been best guessed at, the white "bands" and other colours are based on a brief colour image of the flag in the film titled Der Führer-besuch in Rom und Neapel at this link [3] at 0:13, combined with images of other fascist flags and banners it appears to have golden yellow and silver. The wood color used can be also seen at colored images from Hitlers visit to Italy in 1938 here and here. The flag can be seen in a image waving beside the Italian national flag here from 1938 and waving behind Mussolini here in 1942. The book Fascism and theatre: comparative studies on the aesthetics and politics of performance by Günter Berghaus on page 90 describes the use of "the [Italian] tricolour and the black flag of Fascism" in 1934 that "were raised onto the façade of the entrance hall, where throughout the day they were protected by a guard of honour."

Flag of the NSDAP during 1920 to 1945. Flaga III Rzeszy niemieckiej.

Autor: Sfs90, Licencja: CC BY-SA 4.0

Flag of the National Socialist Movement of Chile between 1932 and 1938