Wyspa Kalifornia

| Ten artykuł od 2015-06 wymaga zweryfikowania podanych informacji. |

Wyspa Kalifornia – błędne określenie Kalifornii jako wyspy, datowane na XVI wiek. Sądzono wtedy, że Kalifornia była oddzielona w całości od kontynentu amerykańskiego przez cieśninę, a nie, jak obecnie wiadomo, przez Zatokę Kalifornijską.

Jest jednym z najbardziej znanych błędów kartograficznych w historii, propagowanym na wielu mapach w XVII i XVIII wieku pomimo wielu sprzecznych dowodów od wielu badaczy.

Media użyte na tej stronie

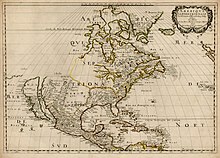

Map of California as an island. Ink and watercolor with pictorial relief.

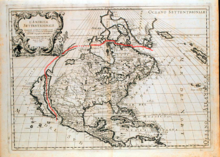

A map that fundamentally impacted the cartographic history of America, this is the 1698 Friar Hennepin map of North America. Covering all of North America from the Equator to the Arctic, this map is remarkable on a number of levels including its depiction of California as an Island, the addition of Terre de Iesso in the extreme northwest, the presence of Lake Apalache in the southeast, the inclusion of Lake Parima and El Dorado in South America, and the suggestion of a Northwest Passage. However, it is best known for its remarkable and highly influential rendering of the Great Lakes and the Mississippi Valley. In 1679 the French lord René-Robert Cavelier de La Salle set out from Fort Frontenac, on Lake Ontario, to explore the Great Lakes and eventually make his way into the Mississippi River. La Salle was of the belief that the Mississippi connected to other water routes that would eventually lead to the Pacific. His scribe and chronicler on this expedition was a Dutch Friar of the Franciscan Recollect order, Antoine Louis Hennepin. Hennepin, who had a passion for “pure and severe virtue” and La Salle, who had a passion for “moral weaknesses” never quite saw eye to eye. Nonetheless, the expedition sailed (and were the first to do so) through Lake Ontario, Lake Erie, and Lake Huron into Lake Michigan, then followed the St. Joseph River to what is today South Bend Indiana, where they constructed Fort Crevecoeur, present day Peoria, Illinois. At this point the explorers parted ways with La Salle returning on foot to Frontenac to resupply and Hennepin continuing onward via the Illinois River to the Mississippi. Hennepin attempted to explore southwards towards the mouth of the Mississippi but, in his own words, “the nations did not give us the time to navigate up and down this river.” Instead he traveled northward past St. Anthony Falls and modern day Minneapolis to Lac des Issatis (Leech Lake), a source of the Mississippi. From here Hennepin attempted a return to Fort Crevecoeur, but was instead captured by a band of wandering Sioux who took him to the Mille Lacs region of Minnesota, near Lake Superior. Hennepin remained in Sioux custody until the adventurer Daneil Greysolon Delhut, who had negotiated a peace treaty with the Sioux, ransomed him. Hennepin and La Salle never met again. La Salle went on to explore the length of the Mississippi, named Louisiana, claimed it for France, and established a short lived colony near Matagorda Bay, Texas. Hennepin, who had enough adventure, returned to France where he published an enormously popular book, Description de la Louisiane . This book featured a map that depicted a speculative course of the Mississippi, but did not suggest any exploration of the southward path of the River beyond it conjunction with the Illinois. Ten years later La Salle was been assassinated in modern day Texas by Pierre Duhaut. Meanwhile, Hennepin, perhaps seeing an opportunity for self-aggrandizement, fled to England (it is William III of England who’s arms appear in the title cartouche of this map) where he published another book, Nouvelle Decouverte d’un tres grand Pays Situe dans L’Amerique and another map – this one. In his second major work Hennepin suggested that, for fear of La Salle, he had hidden the full extent of his explorations: This is where I would like all the world to know the mystery of this discovery that I have hidden until now so as not to inflict sorrow on Sieur de La Salle, who wanted all the glory and secret knowledge of this discovery for himself alone. This is why he sacrificed several persons to prevent them from publishing what they had seen and from foiling his secret plans. In his second enormously popular work; Hennepin claimed that he had explored the full length of the Mississippi before La Salle.

Map of North America by Guillaume Sanson, Rome, 1687. Estimated position of Strait of Anián is marked.